I enjoy novels focusing on a character whose motivations and questions mirror my own darker side. Two recent examples, The Magus (John Fowles) and The Magician’s Land (Lev Grossman), both explore the plight of the young man, and what is he to do? The Magus is a cryptic chasm of false starts, true shocks spiraling the narrative down a hole so deep, I don’t know if I’ve climbed out yet.

There were so many times I asked the very same question the main character did, he might as well have been me. What just happened? Was I there? Who is in on this? Is anybody in on this? What does this all mean? Questions still flood my memory and I’m unable to breach the surface to breathe. What just happened? How am I 31? Did I really do that play? Were they laughing at me? Did I say the wrong thing at a social gathering six weeks ago? Is everybody aware I said the wrong thing? My inner frustration grows, moreso when I’m not even sure if I should do something about it.

The Magician’s Land fueled my love for fantasy and then some. While I can’t weave magic like Quentin Coldwater, I’m still reluctant to admit I do have power I didn’t ten years ago. My knowledge and strength are no doubt greater and I’ve experienced many things. I’ve visited far-off lands (Sackville, New Brunswick is hardly Fillory, but it’ll have to do), met extravagant personalities and found a woman who is one part beautiful, two parts patient. She will live with my shortcomings because she cares deeply for me and I her. But I still don’t know what to do. All I know is I’m addicted to fantasy and I’ll go to great (legal) lengths to fulfill that thirst.

I find myself struggling to identify with younger characters in the games I play, undoubtedly because I’m getting older and wishing to learn more about those who have seen and been around for many years, as opposed to a righteous young upstart whose personality seems to contain only fierce loyalty to their friends and a heart of gold. Or a child with great power, who often has the most annoying voice in a game. I can cast aside such inclinations for games like Blue Dragon, a cast full of children (and the most annoying voice in Marumaro) who embody a lot of clichés but also a lot of fun. When I ponder all the RPGs I’ve journeyed across, I can’t help but realize my recent favorites revolve around older, more conflicted characters, if not my age, then certainly not teenagers or children. Yuri Lowell from Tales of Vesperia is a shining example of a type of character I want to see more often.

Tales of Vesperia is largely agreed upon as one of the best of the Tales series, and certainly a worthy contender for one of the best traditional RPGs of last generation. The soundtrack is unique, hard-hitting and emits an atmosphere that truly thrives. The battle system is lightning-quick and encourages tactics other than button mashing and grinding. I don’t remember full details of the story, but there are two scenes that really stood out for me and propelled Yuri into one of the best protagonists I’ve controlled, and not because of his shining personality or his yearning to protect his friends.

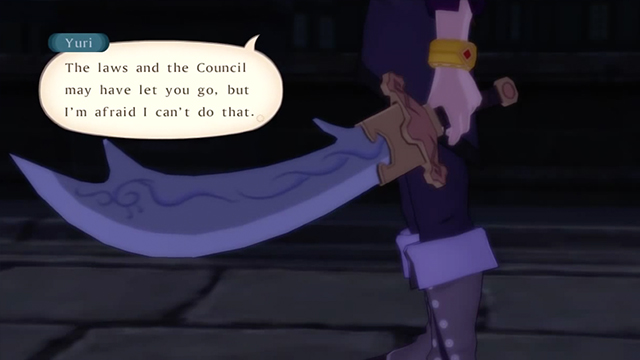

After defeating a notoriously evil enemy, Yuri has found out a collaborator with said enemy is going to get off lightly because of his position on a governmental council. Ragou is truly a nasty example of corruption; he won’t have to answer for his crimes, which include imposing punishing levels of tax, kidnapping and murdering citizens and feeding the dead bodies to monsters, or selling them for profit. Here we see Yuri’s strong sense of justice, right or wrong, prevail. He disguises himself, murders Ragou with his sword and dumps him into the river in the middle of the night. The dialogue isn’t Oscar worthy, but the scene’s impact is undeniably powerful for many reasons.

Primarily, this isn’t predictable behavior for a “good guy.” At the time, I guessed we would live to fight another day and take out Ragou in a more noble and acceptable battle. But Yuri, being the wise old age of 21 (seriously, that’s ancient for a Japanese RPG cast member), has seen things. He’s a former soldier who lives among the poor. He’s sick and tired of seeing how they’re treated, constantly belittled by the upper class, and physically can’t stand to see another example of injustice. His experience in life has led him to make this terrible decision… but is it so terrible?

Another brilliant move was to let Yuri live with his decision without getting caught. Oh sure, people might have suspected he did it, or allude to the fact that it’s quite a coincidence Ragou ended up dead while Yuri was around. But as far as I can remember, he never answers for his crime. There’s no trial, no arrest and no shameful finger wagging by his fellow party members. Ragou is dead, and it’s time to move onto the next adventure. What? He deserved to die. Tell me the world isn’t a better place without him gone.

I found myself fascinated by this scene and its implications. A protagonist with a shade of gray? Somebody who will do wrong to do right? Unbelievable. Yes! This is what I wanted! With the insane range of powers these fictional characters possess and conflicts arising all the time, why shouldn’t the final blow be delivered on a dark bridge under questionable circumstances? Why can’t the villain die unless they’ve transformed into a demon and been given a fair fight? I can’t identify with the notion of murder, but I’ve certainly read about people in positions of power who abused it and wished harsh, swift justice upon them. Who hasn’t?

Yuri, now labelled as a vigilante, strikes again. This kill is far more brutal, and effective; Cumore begs for his life as Yuri edges him off into a sand pit to drown under a dune. Yuri watches and doesn’t move a muscle. Cumore is another disgusting example of humanity who has forced people to work in slave labor camps and sent innocent people to their deaths on a fruitless mission to the middle of the desert. A whimpering coward to the end, he pleads with Yuri. “P-please no! Not like this! I-I don’t want to go like this!” Yuri is having none of it. “Tell me,” he says. “How many times have you heard those very words?” As the shrieks turn to gargles, Cumore is soon gone forever. Our protagonist simply stares and watches, silently confirming to us the deed is done.

It’s quickly revealed that forces of good gain control of the nearby town and the citizens’ lives will be spared going forward. Was Cumore’s death necessary? It’s almost irrelevant; to Yuri, it was unquestionably necessary. He’s probably seen a dozen Cumores escape only to do harm again. And now that he’s done it once, he probably doesn’t think twice about doing it again.

Sadly, the game doesn’t focus much more on this storyline. There are twists and turns and a satisfying ending, but I would have loved for the game to be more about Yuri’s dark side. What would all his friends say if they discovered the gruesome details of how Yuri took the law into his own hands? Would he be able to justify his actions? How would he argue his case? Would he serve any time for his crimes? Would there be a dramatic courtroom scene, like in Chrono Trigger? I can hardly call it wasted potential, since I enjoyed the game to no end. But I’m certainly keen to see this kind of route traveled again.

I suppose the vigilante angle doesn’t have to come from somebody with a bit more experience under their belt. Notions of honor, justice or anger are not exclusive to the more mature crowd. City of God is a tremendous example of what youth, anger and power can result in. But, I’m no longer a kid. I’m not a teenager, unaware of who I am. I’m older. I know who I am. I’m still uncertain about the world, and what to think of it, but I’d like to experiment with those feelings while I swashbuckle through an adventure with somebody closer to my own age and experience. Give me Tales of Vesperia 2 and a focus on Yuri’s darker actions, and I am absolutely there.