Most retrogaming discussions tend to focus on the most evergreen design elements of each title. The controls, the art direction and graphics, the little nuances of level design… they are often the focus, the measure against the tide of time and the reason they stand up against their dated brethren.

But there’s also value in those more ephemeral designs, those clear products of their time. Retrogaming is not just about the age of the games but a different experience, a different frame of mind and goal. It’s a vindication of the past and all the greatness that was in it. And no game shows it better than The Tower of Druaga.

The second game by Xevious creator Masanobu Endo, The Tower of Druaga is virtually unheard of outside of Japan. In its home country, though, it was the game to beat, the arcade masterpiece that influenced every single game creator and the franchise that got an anime thirty years after it was first released.

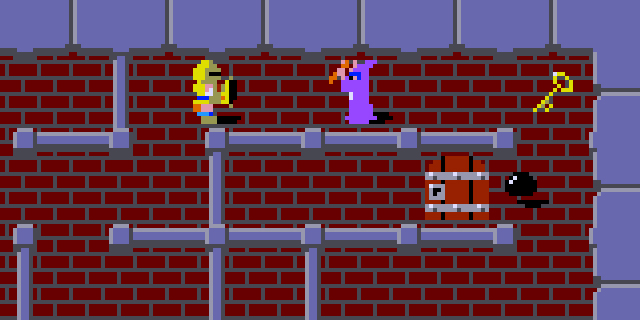

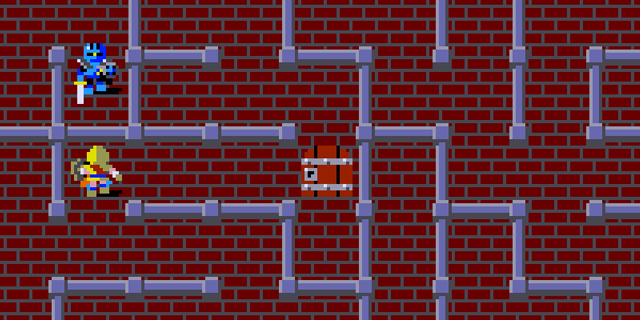

Using the Epic of Gilgamesh as its backdrop, The Tower of Druaga pits the player against the namesake structure in a mixture of maze game and early action-RPG that is surprisingly compelling. The tower is 60 stories high and filled with monsters, evil wizards and deadly traps; only a smattering of helpful items aid the hero in his quest. Cutting down walls, using a magical chime to find treasures and using the power of the Blue Crystal Rod (the only weapon capable of defeating Druaga), you must slowly move up the tower, treating each new floor as a new challenge.

There’s a trick, though: how to obtain those items isn’t explained anywhere in the game.

Nowhere at all. You have to read between the lines, squint your eyes, think and solve an unwritten riddle to get them. It starts easy, killing three of the slimes on the first level and stepping on the door before collecting the key on the fourth, but soon the game starts getting creative. You have to avoid killing any enemies, make a wizard appear on a specific place, press the start button, block a spell and let time run out. It looks like a terrible, impossible-to-solve design. A joke by an already-successful Endo.

But the game can be beaten. You only have to think as they did in 1984.

You know there’s an item in each level. You don’t know how to make it appear, but you know it’s there. So you try stepping over the door. You kill everything and you look for suspicious wall patterns. And you find one. You burn out the timer on the 14th floor looking for clues and get a potion as reward. You start trying wilder stuff, solving the game’s secrets, pulling your hair as more and more wizards appear and navigating the mazes becomes harder and harder. You start taking notes and skipping items you don’t need any more, finding new ways to beat each level. Soon you reach the 59th level and face Druaga. And you’ll know exactly what to do.

It’s perhaps baffling and surely not for everyone, but it’s possible. More than that, it’s incredibly entertaining. The Tower of Druaga is not a Japanese delusion. Like the entrance to the dungeons in the original Legend of Zelda or the warp pipes in Super Mario Bros., it’s a matter of old-school thinking, of communicating with the player without marking the wall or giving you the key to the puzzle. You aren’t expected to solve it. You aren’t expected to win. And once you shed all those modern expectations, there’s nothing preventing you from having fun.