I’ve never understood any real-time strategy game.

I just haven’t. As much as I loved Red Alert and spent half of my early Internet days playing Age of Empires and Starcraft, I realized that I didn’t understand the games I was playing. Sure, I built units, chopped down trees and made a coordinated attack on the enemy base with a quite-brilliant paratrooper plan, but at no point did I question what I was doing or even cared about the options the game was giving.

Total Annihilation was the first time I was told that having options without understanding them is as good as not having any. And I loved every second of it.

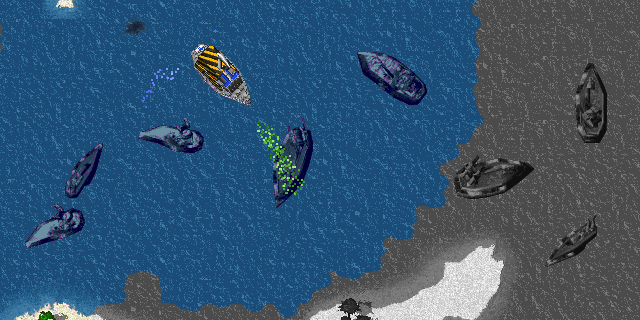

Total Annihilation is just overly direct and brash. While other games let you overrun any fortified opponent given enough Rocket Infantries or lowly Grunts, a failure to choose the correct unit in this game is a horrible setback you take ages to recover when all your fast tanks are annihilated by a couple Laser Towers. Turtling isn’t safe when your resources are taken over by artillery units shooting from the other side of the map, and failure to control the seas is even more punishing than it was in Warcraft, taking smart tactics and cunning wit to turn the tables on your opponent.

Surprisingly, all those sharp points and demanding strategies don’t make the game hard to play, at all. In fact, they teach you to play, showing you which units are useful in which moments and when they are useless, reserving more advanced interactions for later. Because this isn’t a game about timely rushes; each unit is worthwhile because of what it can counter on the battlefield, and while progression is certainly a factor, the core of the game is this interaction, this constant fight of unequal forces and how to maneuver them against your opponent.

Because you don’t simply beat them with a strategically superior force, this is not a game about scouting either. It’s a game where you have to build the rock, the paper and the scissors and use them all at once while scavenging the metal of destroyed units so you can keep pushing against an ever-growing enemy. The battlefield soon grows and grows, and the units fight by the hundreds, your factories sending your robots to the breach as soon as they finish building.

The game has a gigantic scope, with hundreds of units per side. There are no food limits and no population, only the power your machine can gather while running the game. Given the game was designed for early Pentium computers, there’s nothing preventing you from having a thousand units, if not more.

This scope also forces you to consider time. With so many units, so many different battles and so many resources to gather to keep fighting, micromanagement isn’t a skill reserved for Korean pros, but a basic need that oils the engine of the game. Soon you start looking for hotkeys and chaining orders, trying to gain the smallest of edges and slowly taking over the map. Your shipyards are being destroyed and there’s not quite enough metal, but you have to keep pushing, keep working, keep having fun.

Of all the strategy games I have played, this is the tightest. There’s no space for error, everything’s there for a particular reason and every single unit, map and mechanic has the strong grip of the designer’s hand. The graphics are still nice and workable, and the amazing orchestrated soundtrack is still one of my favorites to this day.

Editor’s note: a spiritual successor to the game, dubbed Planetary Annihilation, was successfully Kickstarted last year and is set for a release sometime in 2013.