Strider can be beaten in less than ten minutes. It has fixed enemy patterns and a conscious level design, with enemy attacks based on cold, strict logic. It’s perfectly fair, and health refills are dropped like candy. Sounds easy, right?

It isn’t.

Strider can be beaten in less than ten minutes, but before that comes 20 or 30 hours of practice. Its fixed enemy patterns will get you, if you don’t plan ahead and treat enemy placement as a puzzle to solve. It’s perfectly fair, but if you ever find yourself needing those health pickups, you are already losing ground.

So it’s not exactly easy. But does that matter?

Like many arcade games of its time, Strider isn’t designed to be beaten. There’s no big payoff, no big arc, no big narrative. The game practically stops. This is a game about jumping and slashing. There’s no jumping and slashing when it ends!

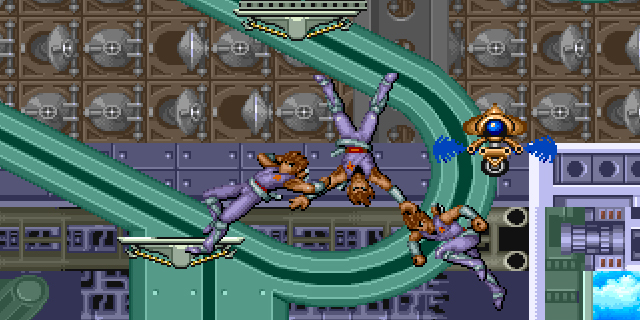

It’s the learning process that matters in Strider. If you already know how to do it, it tells you to go faster, letting you kill the bosses in less than a second and dashing through the enemy defenses. The game refuses to repeat itself, and becomes faster the better you become, a mark of great design. There’s barely any level design in the traditional sense; it’s all in the enemy placement. So you first learn how to face an enemy from behind and above, and from there you must learn everything: how to destroy flying drones, how to kill foes guarding ledges and how to exploit the game’s controls to your advantage.

Because those controls are great! It seems silly to praise a game for this, but how your character can grab practically any edge, climb any surface and do back flips to avoid enemy attacks is so amazing that sometimes I just want to fool around with it a little. It gives the game’s movement a great texture, and forms such a big part of the game that I’m not surprised by its name.

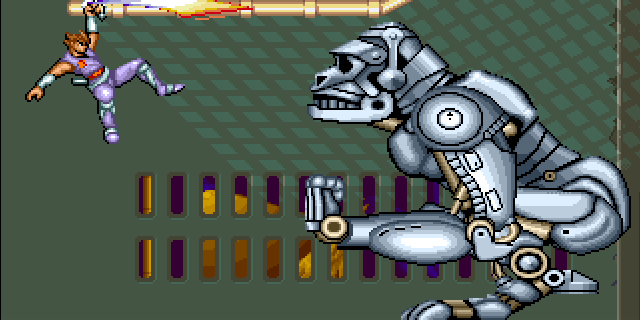

Beyond the mechanical successes, Strider is also big on looks and interesting moments. There’s ingenuity beyond the colorful spandex, and clichés from ’80s action movies are simple raw fun. Like the Russian communists who fuse themselves to form a giant centipede armed with a hammer and a sickle, or the pair of moving walls you must hastily climb before they close and crush you. There are ninjas, dinosaurs and robots. It’s all very entertaining.

The game must have some coding issues, though, because it’s easy to find some bugs. Sometimes the enemy sprites disappear while attacking for a couple of frames, and there are some platforms you can slip through if you aren’t careful. They are not game-breaking, but stick out given the controlled nature of everything else, and will probably be the key factor for potential players when it comes to choosing which version of the game to play.

The original arcade game is perfectly replicated in the most modern ports, notably Capcom Classics Collection, Vol. 2 (PS2/Xbox). The code was slightly cleaned in a two-disc PlayStation release with its (perhaps not quite as good yet still interesting) sequel, so perhaps it’s better to keep those old discs around. Nostalgia seekers may want to try out the Genesis port, which is surprisingly faithful but bears some terrible collision issues.