Myst is a great game.

That used to be the consensus, but it’s a controversial opinion to hold now. One of the bestselling games of all time. It was the software that sold us the compact disc, the game that broke all kinds of critical records and the game that made The New York Times realize games could be art. But newer voices haven’t been so kind.

“Too abstract,” say some critics. “Can’t be good, it’s practically plot-less,” say others. The praise of The New York Times was replaced by the disdain of Roger Ebert, and 1Up’s Jeremy Parish notes that many accuse the game of causing the downfall of the entire adventure genre. The puzzles started to gather complaints, and the prerendered backgrounds, one of the flagship features of the game, started to feel dated in the minds of many.

Some think Myst was a mistake. But I’m certain it wasn’t.

Many approached the game after trying the titles of LucasArts and Sierra, and walked out disappointed with the non-existent characterization and the minimal plot. But it’s not fair to Myst. Myst is not Monkey Island. It’s an abstract game. It sported a tagline describing it as a surreal adventure, and it was never meant to have dialogue trees or much of a plot. It was touted as a mental experience, and it certainly never hid its slow, solemn pace.

When you first start the game, hopefully with the lights down and the speakers at a high volume, you see a book fall from the sky. This is a cinematic; no interaction is possible. Yet soon a cursor appears, and you are taken from your seat and told to open it. It’s not an order. Like Adventure, this is a game that you feel has no guidance beyond what’s shown on the screen. There’s no designer, at least not in the normal sense. He’s gone; all that’s left of him is his thinking, abstracted to the subtlest of degrees.

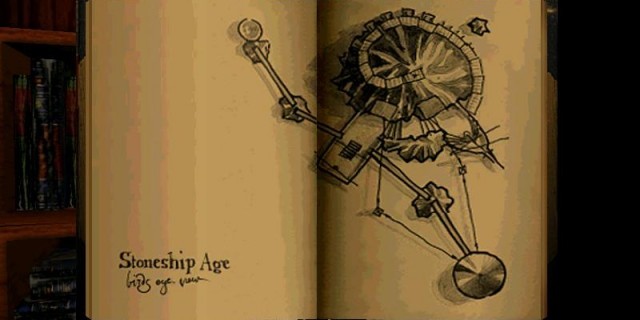

There are clues, though. It’s a surprisingly tight title, once you decide to analyze it. But walking down what looks to be a wooden dock, the sight of the mountain with its unnatural gears sticking out in the distance is something you feel bound to. You decide to explore it, because it’s there. It’s a powerful feeling, yet one that is easy to miss.

Many would feel bored at that point. They would feel lost and yell at the ambient music. But the music can’t answer. It doesn’t exist. You are alone on an island. It’s not a matter of difficulty. The machines and puzzles aren’t real. It’s all in the mind, like Pente or Chess. It’s a purely intellectual feeling, that of seeing your mind ruminate.

If you get into it, the game is immersive. You slowly sink into it, even when you are walking or waiting for the train. It exasperates you, too. It requires a relaxed state. It won’t give. Any reaction would need to arise from the soul of the player.

Have you seen Mad Max? It’s a similar movie, with completely different setting and themes. But the slow, widescreen landscapes and the nonexistent plot make it as harrowing and as boring, for many of the same reasons Myst is. Most would prefer the sequel, but it’s a completely different film.

This is not to say Myst is flawless. Given the parallels to movies, it would only be appropriate to praise its fascination with machines and nature and dismiss its treatment of the human in-betweens.

The graphics have certainly aged, and even the version known as realMyst (from which this article’s screenshots are taken) don’t look too great. But it never once mattered, as it was not the appeal of the game. Fashion changes, but style endures.