In From Pixels to Polygons, we examine classic game franchises that have survived the long transition from the 8- or 16-bit era to the current console generation.

The franchise that famously saved Square from its looming demise in the NES era, Final Fantasy has gone on to define a genre for many. It’s done so by not shying away from change, and the result is a convoluted path of series evolution that’s doubled back on itself as many times as it’s stepped into uncharted territory.

Defining a dynasty

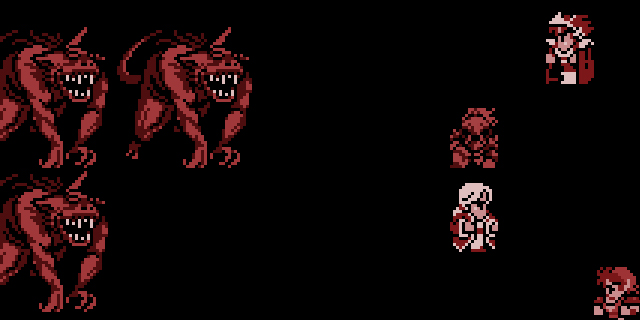

Final Fantasy was among the first JRPGs to utilize a party-based battle system, as well as individual classes for each party member. It laid down many tropes of the genre that we take for granted today: elemental-themed dungeons, a third-person battle perspective and the overworld-traversing vehicles such as airships. While the game’s story was practically nonexistent and the customized characters weren’t nearly as strong as the protagonists of Phantasy Star, Final Fantasy crafted a world that was nevertheless enticing and wondrous. it pushed the NES’ limits, with stunning battle animations and large, detailed sprites.

Final Fantasy was among the first JRPGs to utilize a party-based battle system, as well as individual classes for each party member. It laid down many tropes of the genre that we take for granted today: elemental-themed dungeons, a third-person battle perspective and the overworld-traversing vehicles such as airships. While the game’s story was practically nonexistent and the customized characters weren’t nearly as strong as the protagonists of Phantasy Star, Final Fantasy crafted a world that was nevertheless enticing and wondrous. it pushed the NES’ limits, with stunning battle animations and large, detailed sprites.

It was the sequel, however, that demonstrated how the franchise could have staying power. By putting a greater focus on story and characters, Final Fantasy II started molding the series into what we know it as today. Abandoning the roll-your-own character setup of its predecessor, Square could spend more time ensuring that the player’s experience was more curated and more entwined with the plot. Using a controversial stat-based leveling system (Somewhat similar to what we see in western RPGs today), Square proved that it wasn’t afraid of trying out new ideas, even with its most successful franchise.

Final Fantasy III tried to reconcile the differences between the character customization of the first game and the narrative focus of the second, introducing the class-job system. Pre-set characters could swap between various ability and statistics sets for hundreds of different party combinations. This mechanic allowed gamers a level of control over their play style that had not yet been seen in JRPGs. The game introduced another series staple: summons. – Chris Dominowski

Deeper ambitions

The first to tell a sweeping narrative, Final Fantasy IV had characters with distinct roles, each contributing to the plot. Characters would come and go, and some would never return, despite their time in the party. The game also debuted the Active Time Battle system, in which both heroes and enemies would input commands in real time instead of simply waiting for their turns. Overthinking a decision could be costly, and even lethal. The fifth game revamped and improved a lot of the mechanics that were introduced in earlier games, especially the job system. Party members would earn job points, unlocking abilities available to that class that could be retained when shifting to another, leading to some game-breaking combinations.

The first to tell a sweeping narrative, Final Fantasy IV had characters with distinct roles, each contributing to the plot. Characters would come and go, and some would never return, despite their time in the party. The game also debuted the Active Time Battle system, in which both heroes and enemies would input commands in real time instead of simply waiting for their turns. Overthinking a decision could be costly, and even lethal. The fifth game revamped and improved a lot of the mechanics that were introduced in earlier games, especially the job system. Party members would earn job points, unlocking abilities available to that class that could be retained when shifting to another, leading to some game-breaking combinations.

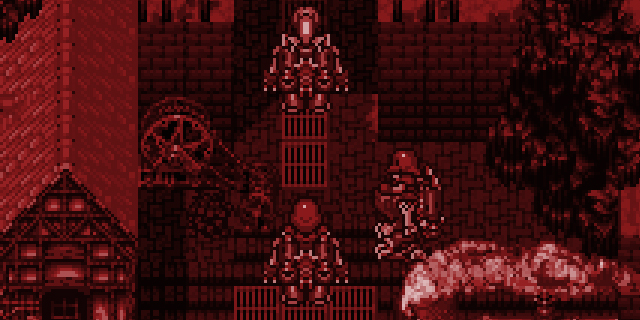

Final Fantasy VI sported one of the deepest plots in the series, as well as branching storylines. Due to the large cast, each character represented a certain class introduced in an earlier Final Fantasy game; Locke was a Thief, Edgar was a Machinist. Occasionally, the story would call for the player to split the cast into separate smaller groups for dungeons. Through the game’s party splits, new characters would be introduced and several antagonists would appear to torment the party. – Eric Albuen

In the global spotlight

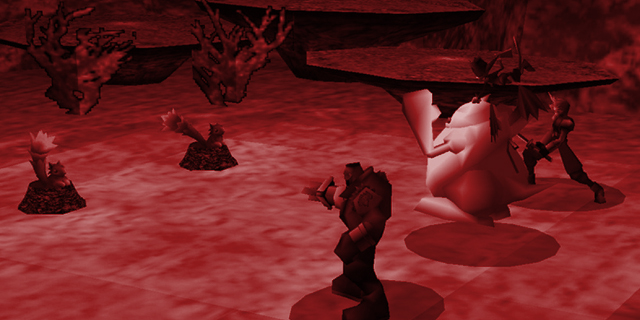

While arguments can be made that Final Fantasy VII‘s story is fairly common within the fantasy genre, what set it apart was the level of detail. With a huge amount of side information and then-impressive cutscenes conveying an intricate backstory, many minor characters are shown to have a large part in the game’s events. While impressive on their own, the way these cinematics flowed into and out of gameplay maintained a connection and avoided the feeling of gameplay simply existing to fill time between scenes.

While arguments can be made that Final Fantasy VII‘s story is fairly common within the fantasy genre, what set it apart was the level of detail. With a huge amount of side information and then-impressive cutscenes conveying an intricate backstory, many minor characters are shown to have a large part in the game’s events. While impressive on their own, the way these cinematics flowed into and out of gameplay maintained a connection and avoided the feeling of gameplay simply existing to fill time between scenes.

It was also the first game in the series to be largely free of audio hardware limitations. If you play a track from VII to someone who played it, it’s likely they can tell you exactly which part of the game you got it from. Without voice actors to convey emotions to the player, the music was often used to fill this role, becoming part of the events on the screen. Final Fantasy VII not only defined the next generation of Final Fantasy, but of console RPGs as a whole.

For VIII, Square continued the modern theme, with certain aspects of the game using a more futuristic setting. It continued the series’ tradition of completely rearranging the battle and magic systems. Magic was instead stocked as a consumable item and could be used alongside summoned creatures to enhance statistics and add elemental damage or statuses to weapon attacks. This gave players a lot of power to tailor their party to suit the enemies in a given area, but amassing magic in this way was often tedious and discouraged players from using it in battle. Discovering good combinations of magic and stats could be rewarding, yet often resulted in a game that held little challenge.

Final Fantasy IX was something of a throwback piece. Largely turning away from the modern theme, IX went back to the pure fantasy setting of the original, with a much brighter and lighthearted theme. Characters had specific classes assigned to them, and the game assigned greater importance to often-ignored elements like stealing items from enemies. The visual change from VII to IX in terms of visual appearance is impressive; at first glance, it looks as if the two games aren’t running on the same hardware. – Jeff deSolla

Exploring modern mechanics

Final Fantasy X showed, more than any other PS2 game, just what that that hardware could do. Spira was a wonder to behold, letting you take in the sights instead of just running from place to place to get the story beats. From the characters to the environments, everything felt like part of a real, living world. Taking a page from Final Fantasy IV’s book, every character has a set role. Tidus was in your party for haste, Yuna there for summoning, and Lulu around to cast black magic. A return to turn-based fighting made attacks feel more substantial. Enemies hit harder, because there is an expectation that you’ll be making better decisions than “hammer on X until everything dies.” It is possible to complete some fights without the enemy ever being able to get off a single attack, thanks to the updated turn order showing up before you execute a command.

Final Fantasy X showed, more than any other PS2 game, just what that that hardware could do. Spira was a wonder to behold, letting you take in the sights instead of just running from place to place to get the story beats. From the characters to the environments, everything felt like part of a real, living world. Taking a page from Final Fantasy IV’s book, every character has a set role. Tidus was in your party for haste, Yuna there for summoning, and Lulu around to cast black magic. A return to turn-based fighting made attacks feel more substantial. Enemies hit harder, because there is an expectation that you’ll be making better decisions than “hammer on X until everything dies.” It is possible to complete some fights without the enemy ever being able to get off a single attack, thanks to the updated turn order showing up before you execute a command.

Final Fantasy XII introduced the gambit system, allowing you to program your allies’ tactics and concentrate on higher-level strategy. It showed us that real-time combat could work and work well in a party-focused JRPG, and the unique gambits gave us a fun way to play that I would love to see again.

Final Fantasy XIII moved back to a sci-fi setting, with an interesting story, likable characters and gorgeous visuals. It’s also stressful instead of fun. While X and XII put the impetus on the player to be in control of battles, Final Fantasy XIII often feels like it plays itself. And when you do wrest back control of the game, your combat scores suffer. It puts an unfair emphasis on getting things done quickly — odd for a series known for 50+ hour save files — instead of getting them done well. It’s also painfully linear. Finding out-of-the-way areas to look for side quests is part of the fun of an RPG, allowing players to form a deeper attachment to the world they’re saving. The story and characters are enough to make it worth playing, but XIII showed us that the ancillary components aren’t just fluff: they’re a part of the experience that players want. – Justin Last

What’s the peak of the Final Fantasy series?

Chris: As a fan of the more simple, pick-up-and-play Final Fantasy games of the Famicom era, Final Fantasy IX really clicked with me. Combining the whimsy and charm of the series’ early days with its newfound focus on storytelling bordering on operatic, it stands out with what made Final Fantasy what it is.

Chris: As a fan of the more simple, pick-up-and-play Final Fantasy games of the Famicom era, Final Fantasy IX really clicked with me. Combining the whimsy and charm of the series’ early days with its newfound focus on storytelling bordering on operatic, it stands out with what made Final Fantasy what it is.

Eric: I’m a sucker for a good story, and I personally believe Final Fantasy VI had the best one in the entire series. To take a huge playable cast like that and make each character unique is a daunting task, and a deep plot with amazing music and characters blooming with personality? It sounds like a recipe for success to me.

Eric: I’m a sucker for a good story, and I personally believe Final Fantasy VI had the best one in the entire series. To take a huge playable cast like that and make each character unique is a daunting task, and a deep plot with amazing music and characters blooming with personality? It sounds like a recipe for success to me.

Jeff: As a fan of old and new, I have to go with Final Fantasy IX. With the wonderful music and cinematic design of the PS1 era and the gameplay of the older games, it’s the perfect combination of all things Final Fantasy.

Jeff: As a fan of old and new, I have to go with Final Fantasy IX. With the wonderful music and cinematic design of the PS1 era and the gameplay of the older games, it’s the perfect combination of all things Final Fantasy.

Justin: Final Fantasy IV‘s story is well-told, the characters all feel like fully-realized people and distinct party members make the combat a ton of fun to play. It was hard not to put X here, though, because if every RPG took that battle system, I’d play them all and love it every time.

Justin: Final Fantasy IV‘s story is well-told, the characters all feel like fully-realized people and distinct party members make the combat a ton of fun to play. It was hard not to put X here, though, because if every RPG took that battle system, I’d play them all and love it every time.

In the next installment, we discuss the jungle platforming of Donkey Kong.