When this column originally ran, it was primarily about playing games with your children. To be perfectly honest, I started writing it early. My kids are all two years old. We play Kinectimals together, and I’m looking forward to playing Once Upon A Monster with them when they’re a little bit older. For the time being, though, I am perfectly happy with them being thrilled to play with MegaBloks, stuffed animals and picture books.

What they have done, however, is permanently affect the way that I view the world and how certain things affect me. One game hit me particularly hard this year: Telltale’s The Walking Dead.

Anniversary profile

Gaming with Children

Author: Justin Last (2010)

Examining how to involve your children in the hobby you love, among other effects parenthood has on your gaming life.

(Be warned: there are spoilers beyond this point.)

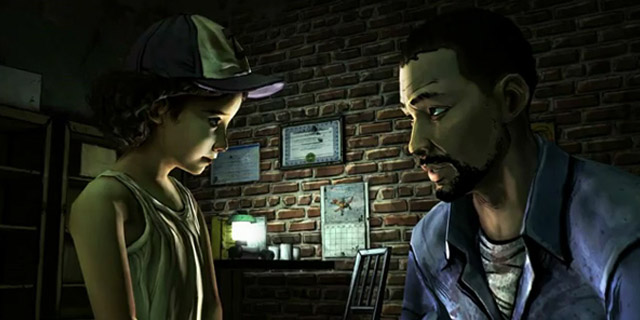

I don’t normally like child characters in games, because developers hamstring them. They’re either invincible or annoying. (Or both.) To properly use a child in a story, you have to use them as full-fledged characters, and Telltale has done exactly that with Clementine. When Lee finds her in episode one, he doesn’t know what to do or how to take care of her; he only knows that she needs protecting.

His journey starts, zombies aside, the same way mine did as a parent. I’d never had kids before, but when I first saw them the day they were born I knew that my priorities had immediately changed. I was no longer working for a paycheck; I was working to ensure that my kids would always have the things that they needed. I have an innate need to protect them, to keep them safe, and it’s clear that Lee feels the same way for Clementine. His life changes abruptly twice in the same day, and he’s a tremendously interesting character for it.

Further cementing the parent-child relationship, Clementine affects the player and the choices that they make. Numerous times throughout the series, you can choose to be supportive or harsh with Clementine, and each time a message pops up informing you that Clementine will remember that. I can’t tell you whether she actually does or if future events take those actions into account, but the reminder that Lee is not a solitary character changes the way that I played.

At the end of episode two, your group encounters a car full of supplies. Playing alone, my instinct would be to loot the car, take everything that I can use and survive that much longer because of it. With little Clem by my side, I couldn’t bring myself to take any supplies from the car. They don’t belong to me, and I don’t want to teach her, especially when the world is coming apart at the seams, that stealing is okay. I need to be better than that, because I want her to grow up to be better than that.

The mirror in my own life here is much smaller. I like to lounge around the house on the weekends. Before I was married, it wasn’t uncommon for me to stay in pajama pants and a sweatshirt all day Saturday with bad movies on the TV and a pan of brownies in the oven. Now, since I want to teach my kids good habits, I wake up early and get dressed so as to not be a hypocrite when

I explain to them that we get dressed and brush our teeth to start the day. It’s not enough to say these things. I have to lead by example, and that’s what Clementine has done to me as a player. The short-term gain in that car isn’t worth teaching Clem to be a bad person.

Episode three shows Lee making hard decisions for Clementine. He can’t afford to be just her friend because he needs to keep her safe. At the same time, she is genuinely helpful, and Lee needs to encourage that. He struggles (or I did, through him) to let Clementine grow up. She’s small enough to fit through the window to open the door, so that we can get much-needed supplies. There’s a good chance of a walker in the building, but the world she lives in is full of danger, and sheltering her will protect her in the short-term and hamstring her in the long-term. It’s legitimately hard to push her from the nest for both her own good and the good of the group, but it has to be done. In the end, Clem is okay. She was scared, she was shaky, and Lee realized she was underequipped, but she’s okay.

The story in The Walking Dead is amazing. The reason it works so well, though, is the fantastically real parental relationship that Telltale has created between Lee and Clementine. I care about that little girl. I know she’s not real, but all of the little things that Telltale included tug at my parental notions, and I spend every moment of gameplay wanting Clementine to be okay. It made me want to strangle Ben and then reconsider because he’s still a kid himself. It made me feel tremendously sorry for Kenny even though he’s a hothead, and it made me feel empathy for Larry even though he’s a distrustful jerk.

Protecting your child awakens something primal in all of us, and it makes the losses harder, the victories sweeter and the story extremely powerful. I recommend the game to everybody, but watch out: if you have kids, you’ll probably end the series in tears. I know I did. I probably didn’t make the best decisions, but at the end I made the only decisions a father could.