Genre 101 is a series that looks at the past and present of a game genre to find lessons about what defines it. This week, guest lecturers Andrew Passafiume and Chris Dominowski unravel the ins and outs of the JRPG.

A world of adventure

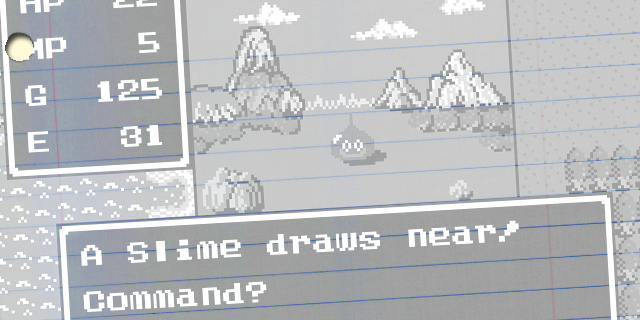

Chris Dominowski: While Black Onyx is generally seen as the first real JRPG, Dragon Quest broke new ground in the nascent genre by giving the Eastern flavor of role-playing its own identity, and began distancing itself from series like Wizardry or Ultima. The game sported a manga-esque art direction by Akira Toriyama, a vast world then unseen on home consoles and a greater emphasis on a top-down perspective. With all that in place, and with future entries in the series depending more on story and characters, Dragon Quest became one of the most celebrated franchises among Japanese gamers.

Chris Dominowski: While Black Onyx is generally seen as the first real JRPG, Dragon Quest broke new ground in the nascent genre by giving the Eastern flavor of role-playing its own identity, and began distancing itself from series like Wizardry or Ultima. The game sported a manga-esque art direction by Akira Toriyama, a vast world then unseen on home consoles and a greater emphasis on a top-down perspective. With all that in place, and with future entries in the series depending more on story and characters, Dragon Quest became one of the most celebrated franchises among Japanese gamers.

Graham Russell: Dragon Quest’s early installments were localized here with a distinctly-Western bent, a trend that generally continued until the genre embraced its roots in the mid-’90s. Do you think this concession to the Medieval European style of high fantasy made it more accessible here, allowing games of its kind to find a foothold in the region?

Graham Russell: Dragon Quest’s early installments were localized here with a distinctly-Western bent, a trend that generally continued until the genre embraced its roots in the mid-’90s. Do you think this concession to the Medieval European style of high fantasy made it more accessible here, allowing games of its kind to find a foothold in the region?

It certainly didn’t hurt. Since role-playing had been almost exclusively dedicated to the realm of fantasy prior (unless you count early 20th-century war games), the familiar setting gave the game a familiar analog for narrative and aesthetic tropes that had grown on role-playing fans prior. You wouldn’t be able to tell it was a Japanese game by playing it.

It certainly didn’t hurt. Since role-playing had been almost exclusively dedicated to the realm of fantasy prior (unless you count early 20th-century war games), the familiar setting gave the game a familiar analog for narrative and aesthetic tropes that had grown on role-playing fans prior. You wouldn’t be able to tell it was a Japanese game by playing it.

Teamwork’s key to survival

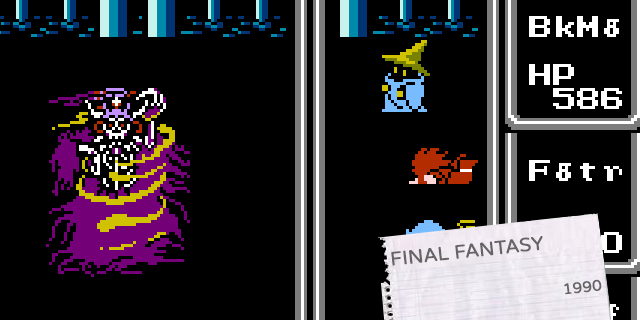

Andrew Passafiume: Yes, Dragon Quest came first and started things off on the right foot, but the original Final Fantasy began a lot of the traditions we’re used to in JRPGs today. It established the idea of maintaining a party of characters with a rudimentary class system, as well as many of the fundamentals of a turn-based battle system that we still see in games today. It’s also the game that saved Square, and essentially guaranteed the franchise would continue for many, many years to come.

Andrew Passafiume: Yes, Dragon Quest came first and started things off on the right foot, but the original Final Fantasy began a lot of the traditions we’re used to in JRPGs today. It established the idea of maintaining a party of characters with a rudimentary class system, as well as many of the fundamentals of a turn-based battle system that we still see in games today. It’s also the game that saved Square, and essentially guaranteed the franchise would continue for many, many years to come.

JRPGs are largely defined by their parties. This comes from the pen-and-paper tradition of gathering with friends and crafting these abilities and roles, but it’s really even more embraced here. What do you think these group-based battles give JRPGs that Western games, more commonly based around one hero, don’t have?

JRPGs are largely defined by their parties. This comes from the pen-and-paper tradition of gathering with friends and crafting these abilities and roles, but it’s really even more embraced here. What do you think these group-based battles give JRPGs that Western games, more commonly based around one hero, don’t have?

The party system is one of the things that set Final Fantasy (and JRPGs in general) apart from most WRPGs, alongside turn-based battles. Entries in the Ultima series, for example, involved a party of characters, but as you said, it was more about the player character. With Final Fantasy, there was no discernible lead. It was about four heroes who set out to save the world. The characters didn’t have much of a back story or even any character at all; they existed to remind players of that group dynamic.

The party system is one of the things that set Final Fantasy (and JRPGs in general) apart from most WRPGs, alongside turn-based battles. Entries in the Ultima series, for example, involved a party of characters, but as you said, it was more about the player character. With Final Fantasy, there was no discernible lead. It was about four heroes who set out to save the world. The characters didn’t have much of a back story or even any character at all; they existed to remind players of that group dynamic.

Developing a narrative focus

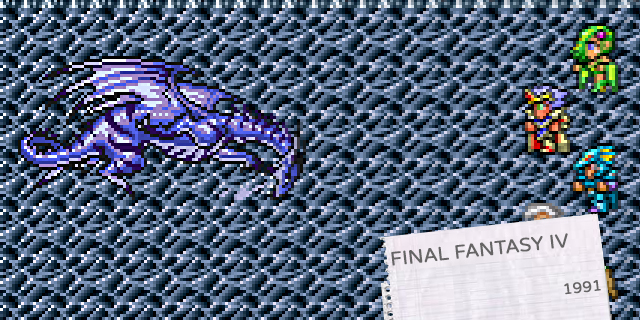

The previous Final Fantasy games had stories, albeit simplistic ones, but Final Fantasy IV is the first game in the long-running franchise that really incorporated a stronger narrative. It expanded the cast of heroes, each feeling less like basic party members and more like actual, memorable characters. The plot even heads in some unexpected directions, and is one of the first games of its kind to incorporate a story as complex as it is. It may not seem like it, but this, along with Sega’s Phantasy Star II, made a compelling story one of the primary reasons to invest in a lengthy JRPG.

The previous Final Fantasy games had stories, albeit simplistic ones, but Final Fantasy IV is the first game in the long-running franchise that really incorporated a stronger narrative. It expanded the cast of heroes, each feeling less like basic party members and more like actual, memorable characters. The plot even heads in some unexpected directions, and is one of the first games of its kind to incorporate a story as complex as it is. It may not seem like it, but this, along with Sega’s Phantasy Star II, made a compelling story one of the primary reasons to invest in a lengthy JRPG.

The 16-bit generation is largely considered to be the heyday for the genre, with myriad installments and a consistent base of mechanics and themes that most games built upon. What was it about this era that made it so fruitful for JRPGs, and why isn’t that the case today?

The 16-bit generation is largely considered to be the heyday for the genre, with myriad installments and a consistent base of mechanics and themes that most games built upon. What was it about this era that made it so fruitful for JRPGs, and why isn’t that the case today?

JRPGs began during the 8-bit era and gained an audience, but it wasn’t until developers starting taking those base mechanics and systems and actually crafting a story around them. This made these games more appealing to those looking for a deeper experience and the games were starting to sell better as a result. Teams were more willing to experiment as well, giving us a larger selection of titles outside of the Final Fantasy franchise. Today, games cost more, and JRPGs simply aren’t doing as well as they used to, even in Japan. The big franchises will continue to (mostly) succeed, but not the same way they used to. Ultimately, the 16-bit era was a time of discovery for both players and developers, and succeeded because these games were trying something different.

JRPGs began during the 8-bit era and gained an audience, but it wasn’t until developers starting taking those base mechanics and systems and actually crafting a story around them. This made these games more appealing to those looking for a deeper experience and the games were starting to sell better as a result. Teams were more willing to experiment as well, giving us a larger selection of titles outside of the Final Fantasy franchise. Today, games cost more, and JRPGs simply aren’t doing as well as they used to, even in Japan. The big franchises will continue to (mostly) succeed, but not the same way they used to. Ultimately, the 16-bit era was a time of discovery for both players and developers, and succeeded because these games were trying something different.

A little more action, please

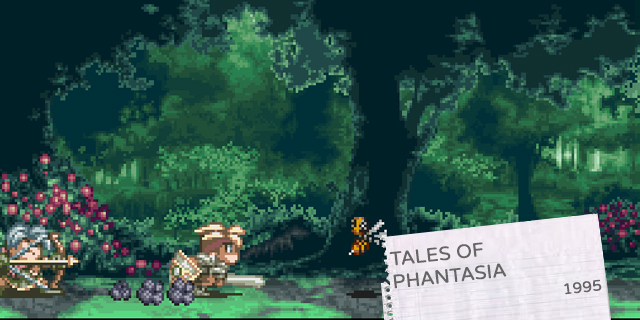

Tales of Phantasia redefined what Japan’s take on the action-RPG looked like, and also pushed the Super Famicom to its limits. Using random encounters and a single 2D plane for the battle system, Tales of Phantasia offered a great deal more fluidity than the roguelikes and isometric games that dominated at the time, creating an experience more in line with a turn-based RPG. It paved the way for later Tales games to capitalize on the formula with features like multiple planes of movement and cooperative multiplayer, the latter of which still eludes most JRPGs.

Tales of Phantasia redefined what Japan’s take on the action-RPG looked like, and also pushed the Super Famicom to its limits. Using random encounters and a single 2D plane for the battle system, Tales of Phantasia offered a great deal more fluidity than the roguelikes and isometric games that dominated at the time, creating an experience more in line with a turn-based RPG. It paved the way for later Tales games to capitalize on the formula with features like multiple planes of movement and cooperative multiplayer, the latter of which still eludes most JRPGs.

Tales of Phantasia is a great example of the localization disconnect that the genre typically faces. It was released in Japan in 1995, but didn’t see the West until a too-late-to-be-relevant 2006 GBA release. What effect do you think this delay, as well as an inconsistent and often contradictory translation and re-translation process, has on a JRPG? Can a game have anywhere near the original intended effect after all that?

Tales of Phantasia is a great example of the localization disconnect that the genre typically faces. It was released in Japan in 1995, but didn’t see the West until a too-late-to-be-relevant 2006 GBA release. What effect do you think this delay, as well as an inconsistent and often contradictory translation and re-translation process, has on a JRPG? Can a game have anywhere near the original intended effect after all that?

The technical mastery that Wolfteam displayed on the Super Famicom was certainly lost in the decade-plus time it took the original to make it over, especially since later titles in the series had since been released Stateside. Because of this, as well as the nigh-nonexistent marketing for the game, it would be easily forgiven if the uninformed regarded Phantasia as little more than a footnote.

The technical mastery that Wolfteam displayed on the Super Famicom was certainly lost in the decade-plus time it took the original to make it over, especially since later titles in the series had since been released Stateside. Because of this, as well as the nigh-nonexistent marketing for the game, it would be easily forgiven if the uninformed regarded Phantasia as little more than a footnote.

A healthy respect for time

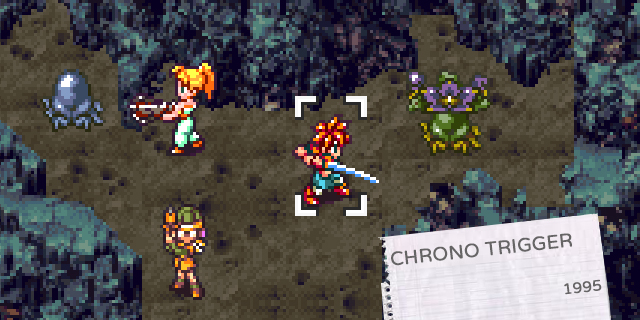

When it was first released, Chrono Trigger was truly something special. It essentially found a way to handle “random” encounters by making all of the enemies visible on the map and the battles taking place directly where you encountered them. It may seem like a small touch, but by subverting the random element it made encounters seem more meaningful as a result. After Chrono Trigger, it began to pop up in several other games, to the point that its basically the standard for JRPGs these days (even if it took a while for the genre to get to that point).

When it was first released, Chrono Trigger was truly something special. It essentially found a way to handle “random” encounters by making all of the enemies visible on the map and the battles taking place directly where you encountered them. It may seem like a small touch, but by subverting the random element it made encounters seem more meaningful as a result. After Chrono Trigger, it began to pop up in several other games, to the point that its basically the standard for JRPGs these days (even if it took a while for the genre to get to that point).

Removing random encounters was a way to try to make the world less abstract and more coherent. Of late, Japanese games have lagged behind in portraying realism, even though they were among the first to put together narratives and worlds. What other steps have been taken to close this gap, and is the genre better for it or should it embrace its quirks and abstractions?

Removing random encounters was a way to try to make the world less abstract and more coherent. Of late, Japanese games have lagged behind in portraying realism, even though they were among the first to put together narratives and worlds. What other steps have been taken to close this gap, and is the genre better for it or should it embrace its quirks and abstractions?

I think JRPGs are still distinct enough from their Western counterparts, even if you’re still seeing developers borrow ideas from WRPGs (and other, similar genres) more often these days than ever before. Look at the upcoming Final Fantasy XV, and how it almost completely abandons the turn-based system that the genre (and series) was at one point known for. That said, I think that distinction is important, which is why recent releases like Ni no Kuni are so successful, both among critics and fans. JRPGs can evolve while sticking with what they’ve always done best, or at least what separates them from other RPGs on the market.

I think JRPGs are still distinct enough from their Western counterparts, even if you’re still seeing developers borrow ideas from WRPGs (and other, similar genres) more often these days than ever before. Look at the upcoming Final Fantasy XV, and how it almost completely abandons the turn-based system that the genre (and series) was at one point known for. That said, I think that distinction is important, which is why recent releases like Ni no Kuni are so successful, both among critics and fans. JRPGs can evolve while sticking with what they’ve always done best, or at least what separates them from other RPGs on the market.

Becoming a phenomenon

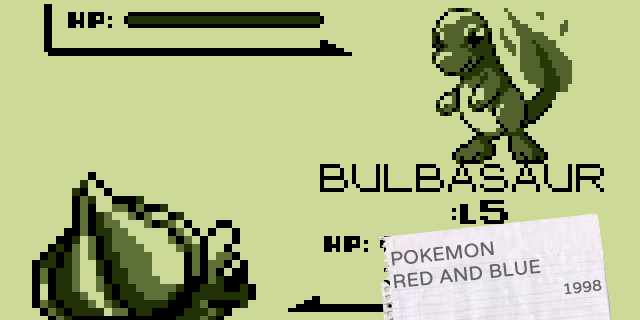

Arguably the first major success in marketing the RPG to young children, Pokémon Red and Blue took the monster-collecting elements introduced in Dragon Quest V and created an entire RPG around it, offering a whopping 151 monsters to collect, trade and train. Moreover, the cross-media push for the game hit the West like a tidal wave, launching an anime, trading card game and toy line all within a short time. This made Pokémon into one of Nintendo’s biggest franchises almost overnight, and the addictive nature of monster collecting ensured its place as one of the most influential series in the genre.

Arguably the first major success in marketing the RPG to young children, Pokémon Red and Blue took the monster-collecting elements introduced in Dragon Quest V and created an entire RPG around it, offering a whopping 151 monsters to collect, trade and train. Moreover, the cross-media push for the game hit the West like a tidal wave, launching an anime, trading card game and toy line all within a short time. This made Pokémon into one of Nintendo’s biggest franchises almost overnight, and the addictive nature of monster collecting ensured its place as one of the most influential series in the genre.

JRPGs have, for the most part, been largely single-player affairs; after all, they’re long and engrossing. The monster-trading mechanic made popular in Pokémon and carried through by imitators over the years was the first to really find a way for people to enjoy their own stories but still interact with others.

JRPGs have, for the most part, been largely single-player affairs; after all, they’re long and engrossing. The monster-trading mechanic made popular in Pokémon and carried through by imitators over the years was the first to really find a way for people to enjoy their own stories but still interact with others.

It was this mentality that allowed RPGs to break into social territory in a much more visible way than early MMOs. The way the game necessitated this social interaction allowed it to spread like wildfire across playgrounds in the ’90s. It was a game that let you feel like king of your own world, while smoothing over the problems that come with using this plot in multiplayer-focused games. We can still see a very similar idea cropping up in multiplayer JRPGs today, like Capcom’s Monster Hunter series.

It was this mentality that allowed RPGs to break into social territory in a much more visible way than early MMOs. The way the game necessitated this social interaction allowed it to spread like wildfire across playgrounds in the ’90s. It was a game that let you feel like king of your own world, while smoothing over the problems that come with using this plot in multiplayer-focused games. We can still see a very similar idea cropping up in multiplayer JRPGs today, like Capcom’s Monster Hunter series.

Broadening appeal through engagement

Super Mario RPG is one of the biggest surprises of the 16-bit era, one that not everyone thought would pan out. Taking one of gaming’s biggest franchises and turning it into an RPG sounds like standard fare today, but back then it was basically unheard of. Thankfully, the folks at Square managed to make something special. It was the first game of its kind to use an action-based battle system, meaning you did more in battles than just select options; you were more of an active participant. This made battles more exciting to those who might find the traditional turn-based battle systems a little dry, and expanded the genre, even slightly, to allow for even more experimental battle systems in the future.

Super Mario RPG is one of the biggest surprises of the 16-bit era, one that not everyone thought would pan out. Taking one of gaming’s biggest franchises and turning it into an RPG sounds like standard fare today, but back then it was basically unheard of. Thankfully, the folks at Square managed to make something special. It was the first game of its kind to use an action-based battle system, meaning you did more in battles than just select options; you were more of an active participant. This made battles more exciting to those who might find the traditional turn-based battle systems a little dry, and expanded the genre, even slightly, to allow for even more experimental battle systems in the future.

JRPGs are built on largely turn-based systems, so combating tedium and keeping interest has always been a concern. Was this a half-step, meant to move toward more active real-time systems, or a viable long-term solution on its own?

JRPGs are built on largely turn-based systems, so combating tedium and keeping interest has always been a concern. Was this a half-step, meant to move toward more active real-time systems, or a viable long-term solution on its own?

At the time, it seemed like a way to win over fans of the Super Mario Bros. games while still making a JRPG as a way to win over two separate audiences, so then it was probably a half-step. But we’ve been seeing more games focused on action-based systems (like Final Fantasy XV) to the point where the traditional turn-based battle systems are becoming the exception. I doubt at the time the developers ever expected the Super Mario RPG battle system (or more action-based systems) to become the norm, yet it was definitely the first of many to steer away from tradition.

At the time, it seemed like a way to win over fans of the Super Mario Bros. games while still making a JRPG as a way to win over two separate audiences, so then it was probably a half-step. But we’ve been seeing more games focused on action-based systems (like Final Fantasy XV) to the point where the traditional turn-based battle systems are becoming the exception. I doubt at the time the developers ever expected the Super Mario RPG battle system (or more action-based systems) to become the norm, yet it was definitely the first of many to steer away from tradition.

The genre’s PlayStation peak

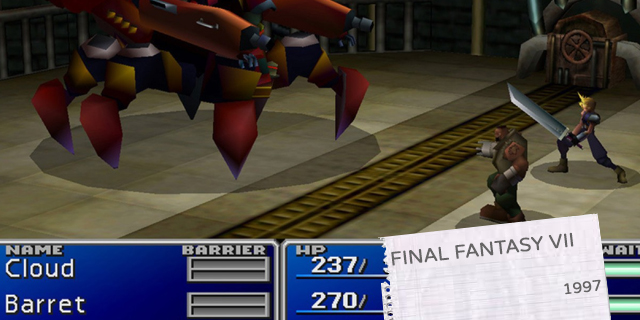

The effect Final Fantasy VII had on the industry and gaming culture can’t be understated. It sparked a gold rush for developers to establish their own presence in the genre, much like first-person shooters of today, making JRPGs the blockbuster genre for an entire generation. There were many FFVII imitators released, but none could have matched the sheer marketing might and social influence that it commanded.

The effect Final Fantasy VII had on the industry and gaming culture can’t be understated. It sparked a gold rush for developers to establish their own presence in the genre, much like first-person shooters of today, making JRPGs the blockbuster genre for an entire generation. There were many FFVII imitators released, but none could have matched the sheer marketing might and social influence that it commanded.

While JRPGs remain relevant and strong and aren’t going anywhere, it’s hard to deny that the release of Final Fantasy VII marked the peak of the genre’s popularity and cultural reach. Do you think it will ever reach those heights again? Will it even be particularly good for the genre if it does?

While JRPGs remain relevant and strong and aren’t going anywhere, it’s hard to deny that the release of Final Fantasy VII marked the peak of the genre’s popularity and cultural reach. Do you think it will ever reach those heights again? Will it even be particularly good for the genre if it does?

I doubt that we will see such a huge worldwide trend happen again. The Western market in particular seems to be pretty set in its ways, in that it wants shooters and western RPGs. Combining that with the rising costs to develop AAA-tier games and the general great length of JRPGs, and you have a situation that is inhospitable at best.

I doubt that we will see such a huge worldwide trend happen again. The Western market in particular seems to be pretty set in its ways, in that it wants shooters and western RPGs. Combining that with the rising costs to develop AAA-tier games and the general great length of JRPGs, and you have a situation that is inhospitable at best.

With a little help from my friends

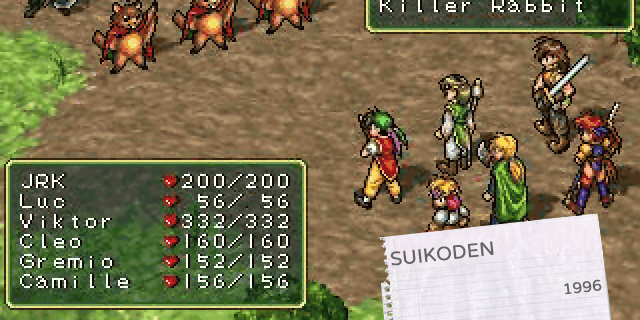

At the time of its release, the original Suikoden was met with a somewhat tepid response, but it laid the groundwork for JRPGs that focused on having a larger party of characters. It’s not a trend you see too often, but back in the day, having a game with that many characters to (essentially) collect and have join your cause was something unique. Its base mechanics weren’t groundbreaking, and its story was simplistic, but this one facet made it a game worth paying attention to and one that showed just how expansive you can be with an already-proven formula.

At the time of its release, the original Suikoden was met with a somewhat tepid response, but it laid the groundwork for JRPGs that focused on having a larger party of characters. It’s not a trend you see too often, but back in the day, having a game with that many characters to (essentially) collect and have join your cause was something unique. Its base mechanics weren’t groundbreaking, and its story was simplistic, but this one facet made it a game worth paying attention to and one that showed just how expansive you can be with an already-proven formula.

How many playable characters is too many? Having this large cast was Suikoden’s thing, but it’s not the only game to throw too many party members at a player to get very attached to any of them. But changing party members is fun. How do you strike a balance?

How many playable characters is too many? Having this large cast was Suikoden’s thing, but it’s not the only game to throw too many party members at a player to get very attached to any of them. But changing party members is fun. How do you strike a balance?

That’s a tough one. I think Suikoden pulled it off because collecting all of the characters was far from a necessity. It was less about a compelling cast of characters and more about amassing an army, which matched the game’s themes. The core cast was still the reason you played, and the extra characters were almost like fun collectibles. It can backfire, though. Chrono Cross was billed as a successor to Chrono Trigger, a game known for its strong cast of characters, yet it took the Suikoden route. Sure, it was only 45 characters versus a cast of 120, but as a result the characters were both less memorable and, at some point, not even worth paying attention to.

That’s a tough one. I think Suikoden pulled it off because collecting all of the characters was far from a necessity. It was less about a compelling cast of characters and more about amassing an army, which matched the game’s themes. The core cast was still the reason you played, and the extra characters were almost like fun collectibles. It can backfire, though. Chrono Cross was billed as a successor to Chrono Trigger, a game known for its strong cast of characters, yet it took the Suikoden route. Sure, it was only 45 characters versus a cast of 120, but as a result the characters were both less memorable and, at some point, not even worth paying attention to.

Time to go to school

Persona 3 was one of the first JRPGs to make social interaction a core gameplay component. This helped bring the game’s cast to life, since it gave character development a mechanical excuse. It also branched out from the standard fantasy setting of RPGs. Perhaps most importantly, Persona 3 used a tactical and fast-paced battle system that emphasized exploiting enemy weaknesses to make each fight feel rewarding rather than tiresome.

Persona 3 was one of the first JRPGs to make social interaction a core gameplay component. This helped bring the game’s cast to life, since it gave character development a mechanical excuse. It also branched out from the standard fantasy setting of RPGs. Perhaps most importantly, Persona 3 used a tactical and fast-paced battle system that emphasized exploiting enemy weaknesses to make each fight feel rewarding rather than tiresome.

You’re right that Persona took the genre to a different and fresh setting, but just as in the past, its success meant that no end of school-based games followed. Dragon Quest meant a high-fantasy sort of focus for most early games, and Final Fantasy VII popularized the future-tech wave of the late-’90s. This isn’t really different from other genres, but in JRPGs, with their emphasis on story, how do you think this emulation of big hits affects how well games can tell stories?

You’re right that Persona took the genre to a different and fresh setting, but just as in the past, its success meant that no end of school-based games followed. Dragon Quest meant a high-fantasy sort of focus for most early games, and Final Fantasy VII popularized the future-tech wave of the late-’90s. This isn’t really different from other genres, but in JRPGs, with their emphasis on story, how do you think this emulation of big hits affects how well games can tell stories?

The thing that sets Persona apart, aside from the aforementioned setting, was its ability to look inward instead of outward for its narrative. Instead of giving you a massive, world-sweeping quest, it had you stay in one city to deal with problems closer to home, with people you saw every day. Granted, it all amounted to cataclysmic consequences, but the scope was what made it special.

The thing that sets Persona apart, aside from the aforementioned setting, was its ability to look inward instead of outward for its narrative. Instead of giving you a massive, world-sweeping quest, it had you stay in one city to deal with problems closer to home, with people you saw every day. Granted, it all amounted to cataclysmic consequences, but the scope was what made it special.

Synthesizing new ideas

These days, you don’t see too many releases that stick with a large audience the same way they used to. Xenoblade Chronicles is one of the rare examples of a game that not only does that, but also manages to subvert a lot of the genre’s tropes. It’s a JRPG that feels in tune with the genre’s past, but evolves just enough to make a case for its future. The open environments, fast travel system, experience bonuses and many other, smaller tweaks make for a huge step forward for a genre that has felt stagnant for many years. While Xenoblade is most likely influenced by the MMO genre as well as games like Monster Hunter, it takes elements from those and makes them its own.

These days, you don’t see too many releases that stick with a large audience the same way they used to. Xenoblade Chronicles is one of the rare examples of a game that not only does that, but also manages to subvert a lot of the genre’s tropes. It’s a JRPG that feels in tune with the genre’s past, but evolves just enough to make a case for its future. The open environments, fast travel system, experience bonuses and many other, smaller tweaks make for a huge step forward for a genre that has felt stagnant for many years. While Xenoblade is most likely influenced by the MMO genre as well as games like Monster Hunter, it takes elements from those and makes them its own.

It’s these MMO and Monster Hunter elements that make Xenoblade distinct. Much like any other genre, the JRPG also needs to incorporate fresh new ideas from other sources. It does occasionally, but it sometimes feels a bit more hesitant to adapt, even if it finds success when it does.

It’s these MMO and Monster Hunter elements that make Xenoblade distinct. Much like any other genre, the JRPG also needs to incorporate fresh new ideas from other sources. It does occasionally, but it sometimes feels a bit more hesitant to adapt, even if it finds success when it does.

This is exactly the current problem with the genre, and why we’ve seen fewer truly successful JRPGs. Xenoblade Chronicles is the perfect modern example of where the genre should head in the future. I’m not saying games should copy Xenoblade completely; just follow its example and try something a little different. I’m not sure if JRPGs will ever become as successful as they once were, but hopefully we’ll begin to see the genre evolve in a meaningful way.

This is exactly the current problem with the genre, and why we’ve seen fewer truly successful JRPGs. Xenoblade Chronicles is the perfect modern example of where the genre should head in the future. I’m not saying games should copy Xenoblade completely; just follow its example and try something a little different. I’m not sure if JRPGs will ever become as successful as they once were, but hopefully we’ll begin to see the genre evolve in a meaningful way.