These days, local multiplayer is a widespread, pervasive thing in the industry, even if many are moving toward online play. That hasn’t always been the case. After all, not many people were playing four-player games in 1987! And more than any other company, Hudson Soft is responsible for changing the world into one that embraces couch play.

Why? Three main reasons.

TurboGrafx-16 and building a multitap engine

Hudson worked with NEC to develop and manufacture the hardware for the PC Engine, released in the West as the TurboGrafx-16, and was its primary supplier of software. It created the system’s CPU. It designed the storage cards. It also put just one controller port on the system, making an incentive for even two-player fans to have to pick up the Turbo Tap accessory.

It supported it with Dungeon Explorer, a quite-difficult take on the Gauntlet formula, and different permutations of Bomberman, which I’ll get to in a bit. More importantly, though, this did two things. First, it gave developers a high attach rate for a multiplayer adapter. That really opens up the possibilities for a dev team, as without wide acceptance, peripherals wither on the vine. Second, it gave Hudson the hardware design experience it would be needing later.

Spreading the word with Bomberman

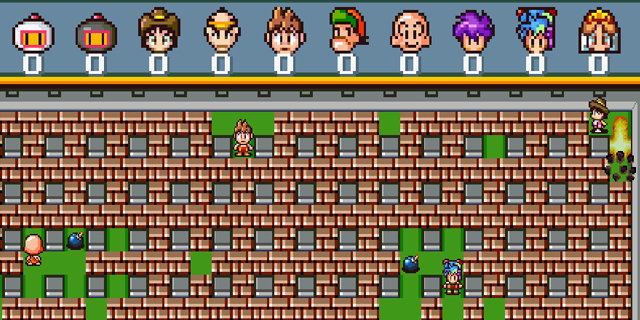

So Bomberman. Regardless of all of Hudson Soft’s successes, it will long be remembered for this one franchise, and that’s totally justified. Even on systems it didn’t really develop for, like the Genesis and the PS3, it scrapped together a version of the explosion-happy title. And everywhere it went, it did what it could to get more people playing.

The Super NES’ multitap? Yep, that’s a Hudson creation, made to drive the Bomberman games it was cranking out after the TurboGrafx faded in the mid-’90s. Saturn Bomberman? It’s the ultimate multitap title (and I’ve talked about that before). Even in the late 2000s, when four-player support had already become the standard, it pushed the envelope with the seven-player Bomberman Ultra on PS3.

What made this effort so successful was Bomberman‘s core design. It’s easy to pick up and play, but there’s definitely skill involved. It plays quickly, so even though players are eliminated, they don’t have to wait around long. Oh, and blowing up other players is fun. Other studios picked up on these qualities, so a lot of what you’re seeing today — even in new games like TowerFall and Samurai Gunn — are built on these ideas.

Mario Party kicks off minigame madness

The parts of local multiplayer gaming that weren’t shaped by Bomberman were often inspired by Mario Party, Nintendo’s mascot-filled minigame collection. Hudson was at the helm of the franchise’s development since the very beginning, and only relinquished control when it was dissolved before Mario Party 9 and replaced by… Nd Cube, a Nintendo studio almost entirely comprised of former Hudson employees.

Whether or not you’ve liked the ensuing deluge of copycat releases (and some, like Sonic Shuffle and Fuzion Frenzy 2, were done by Hudson itself), there’s no denying that Mario Party made games just a bit more accessible. You can tell that the minds at Hudson loved messing with hardware, even that it didn’t make. You see that with its obsession with the Super Game Boy. You see that with its release history including more Sega CD games than Genesis ones. And you see that with its creation of a game concept that relies upon the gimmicks of manipulating controls in strange ways.

This culture was probably largely driven by Takahashi Meijin, a key part of the Hudson team and the inspiration for the main character in Adventure Island. He was known for being capable of 16 button presses in one second, and spawned a Hudson product: the Shooting Watch, a little gadget that simply tested your button-mashing ability. Mario Party turned that sort of skill into something with a bit more context, but still had you moving your fingers like a madman while giving your friends determined looks.

The Mario Party series let people settle down around a TV and play for an extended period of time. It wasn’t fleeting like so many of its peers; it could be a legitimate party, and not just something you do at one for a few minutes. It also spawned some interesting ideas by Nintendo itself: WarioWare took the concept to its extreme with hilarious results, and Nintendo Land built out slightly more complex experiences based on a similar template.

While Hudson was slowly absorbed by Konami over the last decade and no longer exists, its contributions to the industry aren’t going anywhere any time soon. The real shame is that we won’t see the next great leap in multiplayer the company could have brought.