While we must not mistake correlation for causation, no top-selling game system of any generation so far has been the highest technical performer. Alas, history has a tendency to repeat itself. Platform creators can still lose the forest for the trees, neglecting to deliver a quality lineup of software in favor of running glorified tech demos with a high price tag.

Such is the story of the Jaguar, the last standalone console created by former industry titan Atari. Released during an awkward period between the fourth and fifth generations, it promised the world game-changing polygonal 3D visuals and a much-ballyhooed 64-bit architecture. While the Jaguar was cast aside in relatively short order, there are still many reasons to go back to the machine, and its place in history will not be forgotten.

The system

Atari’s Jaguar was intended to be the most powerful system on the market upon its release, with its lauded 64-bit architecture to power it. However, the Jaguar wasn’t a true 64-bit machine. Instead, it had five processors spread out over three chips, creating a system that was downright arcane by reasonable development standards. There were two 32-bit CPUs of equal speed working in parallel in the system: one housing the GPU and a co-processor for shading and Z-buffering, the other handling sound processing with a co-processor for multi-channel output.

To cut down on load times, there was also a Motorola 68000 chip, the same model of chip used in the Sega Genesis and Amiga. However, many developers simply used the latter fact as an easy way to port Genesis games to the system, ignoring the two 32-bit CPUs. Another caveat of this architecture was that since nearly half the system’s muscle was dedicated to sound processing, many developers had to limit or even remove music from their games to get the most out of the system. The most notable example of this was id Software’s port of Doom, which eschewed a soundtrack in favor of keeping the game in full screen.

Jaguar games came on cartridges capable of storing up to six megabytes; it was nothing mind-blowing for the era, but the console eventually received a major upgrade in the form of the Jaguar CD. The Jaguar CD used a special disc format that was capable of storing up to 790 megabytes of data: 90 more than a standard CD-R. Unfortunately, only 11 games were ever commercially released for it, and none took full advantage of the storage space. One notable feature of the JCD: it was one of the first CD players to have an audio visualizer generated in real time. Some demos shown at E3 1995 even used this light show-generation feature for backgrounds.

There were many other add-ons for the Jaguar, many of which were only shown as prototypes and never made it to store shelves. The CatBox was a peripheral released in limited quantities in 1996, giving the Jaguar a host of extra features such as RGB/S-Video out, three audio output sources, two LAN modem ports and a pair of RS-232 I/O ports. Speaking of networks, a modem for online play (with voice chat!) for the system was intended, called the Jaguar Voice Modem. One game was actually released with latent support for the JVM: Ultra Vortek. Some intrepid Jaguar hackers have even found a way to use this feature in a special setup between two consoles.

One networking solution that was released to the public was JagLink, which allowed up to eight systems to be linked up over LAN for multiplayer. The late release Battlesphere Gold even allowed for 32 simultaneous players by connecting eight consoles, with a multitap on each one. Finally, Atari planned and showcased a VR headset for the Jaguar, which was shown at E3 1995 with Missile Command 3D.

The story

Atari had a rough time fighting for the throne of console gaming after the golden era of the 2600 faded away. The 5200 was swallowed up by the US game market crash of 1983, and the 7800 was sat on for ages until Nintendo forced Atari’s hand with the NES. Even the company’s relatively-successful home computer business was struggling to maintain market relevance in the face of Commodore and IBM. Thus, Atari dropped everything in order to make sure its next project would be something truly special. Atari’s solution to its problem? Make the most powerful console a consumer could ask for.

Around the Jaguar’s release, there was a push for realism unlike any other time in the history of the medium. Systems were often marketed using the bandwidth of their processors (8-bit, 16-bit and so on), as it was seen as one of the most simple — although misleading — means of illustrating a system’s technical muscle.

This era is sometimes referred to as the Bit Wars, beginning with the TurboGrafx-16 and ending with the Nintendo 64. Of course, the bandwidth of a processor says little about its capabilities, but to the early-’90s gaming consumer, that didn’t matter one bit. Caught up in the hype of the times, Atari expended most of its advertising budget and energy on promoting the Jaguar as a 64-bit machine, hoping consumers would instinctively regard it as more powerful.

While the Jaguar garnered a great deal of hype about its release in 1993, standout titles for the system were few and far between, and consumers were not willing to patiently wait for the next big thing that may or may not arrive. The Jaguar was soon outpaced in visual and quality content by its contemporaries, such as the 3DO and Sega 32X, both of which were 32-bit systems. That, and the looming threat of even more powerful systems on the horizon such as the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation made Jaguar owners uncertain about the future of their platform. Indeed, in 1996, just a few months after the release of the Saturn and PlayStation, Atari released its final game for the Jaguar, and the company was all but shuttered.

The possibilities

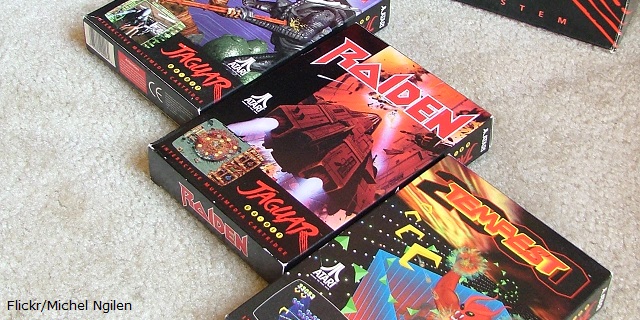

At last count, only 82 games were released across cartridge and CD formats for the Jaguar, although many more titles exist as homebrew efforts. Some standout titles for the system include Iron Soldier I & II, Power Drive Rally, Battlesphere Gold, Tempest 2000, Defender 2000, Alien vs. Predator and Raiden. The Jaguar was originally the exclusive platform for Michel Ancel’s Rayman, which gave rise to one of Ubisoft’s most important franchises. Many of the Jaguar’s best games were not bleeding-edge 3D showcases, as their appeal has diminished with age; the system could instead create remarkably-smooth, crisp 2D visual experiences, many of which hold up far better over time.

Some of the console’s late-release 3D games remain worthwhile due to the sheer technical mastery on behalf of the developers. Games like Skyhammer and Battlesphere push the system to its limits. There’s little debate that the Jaguar wasn’t on par with the Saturn or PlayStation, but such games proved that the system could hold its own when given the benefit of talented developers.

Even today, the system has garnered a cult following of homebrew development teams, who continue to produce new software for Atari’s swan song and resurrect canceled titles. One of the more famous releases has been Black Ice/White Noise, a highly ambitious 3D cyberpunk sandbox game that was cancelled after some work on the JCD. On the way is Atari Owl, an attempt to create a full 3D RPG for the system. Seeing developers putting so much effort into a discontinued system is always heartening to see, and the Jaguar community is one of the most devoted there is.

The Jaguar was a doomed project for Atari, and one that almost bankrupted the company then and there. It was a system that — in retrospect — had everything going against it: a confusing and arcane architecture, an over-emphasis on graphical fidelity over quality titles, a launch too late to gather a user base to survive the forthcoming Saturn and PlayStation and a bizarre, uncomfortable controller.

Despite all this, the Jaguar still has a great deal of charm. It’s quirky beyond compare, had a lot of groundbreaking ideas planned for it and many of its games simply couldn’t have been made at any other place and time. The Jaguar is arguably the most characteristic product of the early-’90s gaming business, for better or worse. In that respect, it’s an essential piece of gaming history. While I can’t recommend that anyone except hardcore retro gamers track one down, if you want to see just what Atari’s final machine had to offer, I wouldn’t dream of stopping you.