The Mystery Machines series looks at platforms that didn’t stay around quite long enough for most to know their stories. For more, check out the archive.

Portable gaming has always been an anomaly when compared to the rest of the industry. While technical prowess is prized above all else on consoles and computers (for better or worse), handhelds rely on their own set of rules. Long battery life and a compact design are far more important than processing muscle when gaming on the go. When these machines were new to gaming, these unspoken criteria were still developing. Nowhere is this bewildering reversal more apparent than in the Atari Lynx, the former console titan’s only major handheld system.

The System

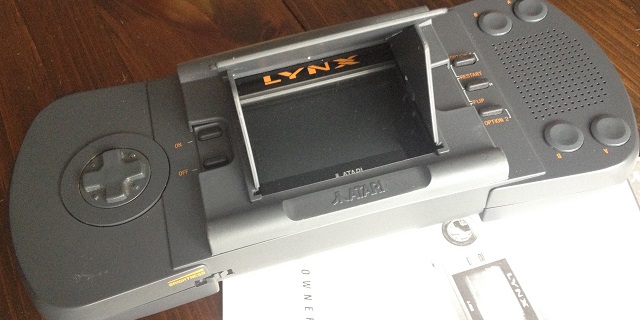

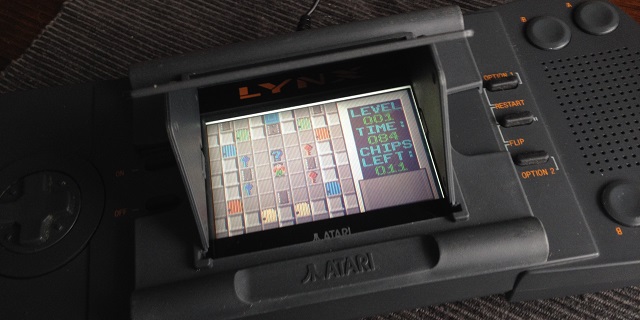

The Lynx was always meant to be the most technically advanced portable gaming experience money could buy. It sported features most home consoles didn’t have at the time, such as sprite scaling and distortion. It was also the first handheld to natively support polygonal 3D visuals, which were mainly reserved for experimental home computer games of the era. In almost every way, the Lynx outclassed its competition in the handheld space for some time to come. Granted, its resolution and CPU clock speed were slightly lower than Nintendo’s Game Boy, but the hardware effects and color screen made the Lynx far and away the superior handheld. Also, in addition to the 8-bit CPU, the Lynx contained two 16-bit coprocessors.

Another nifty feature supported by the handheld was the Comlynx networking system, which allowed up to 18 Lynx units to connect for multiplayer gameplay. While no game ever supported this theoretical maximum (the highest ever supported was eight, by homebrew title T-Tris), it demonstrates the company’s ambition with the device. The Lynx also had a robust development environment, allowing devs tools such as automatic error detection and the ability to test code in a custom emulation environment before sending it to the hardware itself. Such flexibility was practically unheard of at the time. Arcane, time-consuming and costly code testing methods were usually the norm.

While Epyx’s dream machine was a technical marvel, it came with some caveats. First, the model-1 Lynx remains as one of the largest handhelds ever created, with a volume of 10.75” x 4.25” x 1.5”. While a smaller model was eventually released, even that was massive compared to the competing Game Boy and Game Gear. Second, the Lynx’s launch price was $180 — twice the price of the former, coming out a few months after it.

The Story

The Lynx started life in 1986 as a side project at development studio Epyx, when it was dubbed the Handy Game. The team at Epyx — headed by two of the original designers of the Amiga computer — continued development through the next three years, trying out countless different hardware configurations and form factors. During this period, the Epyx team began to realize — being a relatively small software developer — it did not have the brand recognition nor access to supply chains to ship the device on its own. After shopping the prototypes around to different game companies, Atari ended up being the one to proceed with an agreement.

Under Atari’s leadership, the initial prototype saw some major changes. Infamously, Atari asked focus groups what form factor they would like most in a handheld, and the majority of testers claimed they preferred a large, bulky system over a compact one. A joystick was also replaced in favor of a D-pad, and the name changed from “Handy” to “Color Portable Entertainment System”, before being re-branded the Lynx just before release.

After a few months of initial success in which Atari was able to sell through most of its shipments, things quieted down for the Lynx. Sega entered the portable market a year after Atari with its Game Gear, and ate into Atari’s market share more than Nintendo’s, which was proving to be the dominant force in the handheld market. Both Nintendo and Sega had more recognizable franchises to newer gamers, and wasted no time repurposing them for the small screen. The Lynx, however, didn’t have many franchises that still carried weight with the gaming public. Atari had its usual stable of old arcade games, but nothing that would turn heads. This was the Lynx’s greatest shortcoming.

It didn’t help that Atari’s relationship with Epyx was straining. Atari forced vague and punishable deadlines onto Epyx’s software efforts, often making it pay licensing fees to make games for its own hardware, as well as frivolously delaying completed games. This poor treatment of developers weakened support for the platform, as many were already jumping ship to competitors. While a new model and price drop to $100 in 1991 briefly reignited sales, the software library for the Lynx paled in comparison to the competition, and consumers were letting Atari know.

The Lynx lasted until 1994, when Atari Corp. dropped support for it, along with its entire home computer line to refocus all of the company’s efforts on its new Jaguar home console. While internal development lasted until roughly 1996, and independent development still continues to this day, the Lynx died an untimely death at the hands of a desperate parent company.

The Possibilities

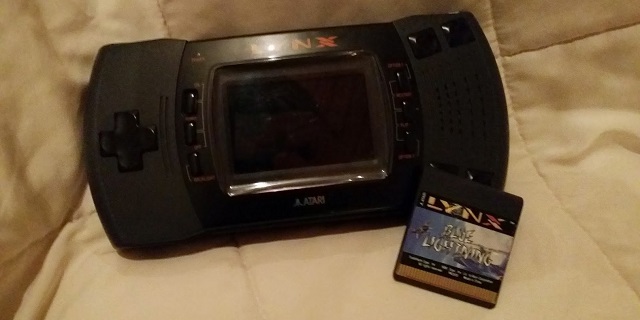

The Lynx was home to some of the most visually and aurally impressive games of its time, thanks to its wide range of hardware-supported effects. The system launched with one of the best games in its library, Blue Lightning. It supported smooth sprite & background scaling that wouldn’t look out of place on a Super Nintendo, and stereo sound effects that used the system’s four audio channels to their fullest. Other games such as S.T.U.N Runner and Hydra were impressive for the same reasons, using the Lynx’s smooth scrolling and scaling to create a convincing illusion of depth that could not be matched until the Game Boy Advance came along over a decade later.

The Comlynx was one of the handheld’s most impressive features, even if its theoretical 18-player limit was never achieved. One game that truly showed the potential of Comlynx was Battle Wheels, a first-person car combat game that supported up to six players at once. Arguably a spiritual successor to Atari’s own Battlezone, the game makes for an intense multiplayer experience few handhelds have been able to match since.

California Games may have been ported to every device with a screen and buttons, but the best version of the game might be on the Lynx. Showing off more of the system’s fluid animation and bold sound effects is always nice, but it is the game’s pick-up-and-play nature and this port’s tight controls that make it a winner.

Atari consoles have a dedicated homebrew community, and the Lynx in particular has some of the most impressive independent software made for a retro system. Some of the more notable titles include Zaku, a Japanese-inspired horizontal shoot-’em-up reminiscent of Air Zonk; sports title Alpine Games, notable for its gorgeously-drawn backgrounds; a port of Wolfenstein 3D; and Wyvern Tales, a Final Fantasy-inspired JRPG.

Finally, the system is well-known for having a slew of unreleased titles, canceled during the period in which Atari was focusing on the Jaguar. Some of these include actual Jaguar ports, such as the FPS Alien vs. Predator and fighter Ultra Vortek. Comlynx functionality was even found left over in the Jaguar hardware, thought to have been disabled during development.

The Lynx befell the same fate as many failed consoles that came before: it was a victim of its own ambition. The system sported hardware that would be unrivaled in the handheld space for over a decade, and the backing of one of the former biggest names in gaming. Alas, the sheer heft of the system (and its price tag), along with a software library without any one killer app, spelled disaster for the fledgling portable. If you are fascinated by hardware ahead of its time, I recommend checking out the Lynx. Most of its best games have never seen a port to other platforms, and even if they have, the graphics and sound of a Lynx are so distinct they would end up being entirely different. Atari’s only major handheld may have been trampled by its competitors, but its fans know it as a system with endless, untapped potential.