Gaming hardware history can arguably be broken down into three distinct categories. First, we have the victors, the ones that rose above the competition to become timeless titans that will remain fondly in gamers’ memories. These are your NESs, PlayStations or 2600s, the ones that many retro aficionados keep plugged into their TVs at all times. Next, we have the forgotten. These systems simply never were able to stand up to the others, and were just swept away by the tides of time, leaving almost no impact on the market. These are your SuperGrafxes, and Atari XEGSes. There’s nothing to show for their existence; they were hardly even a blip on the radar. Finally, we have likely the most interesting category, the infamous.

Systems in the infamous category are certainly remembered, but only for bombing in such a memorable or spectacular fashion that they couldn’t possibly be let go. These are your Atari Jaguars and Philips CD-is. Usually, these systems are far more relevant than the forgotten, since they came much closer to success, while still falling flat. History has been the least kind to these, as they are remembered (fair or not) as eternal jokes by the gaming community. We start off with what many consider to be the strangest and most entertaining story of a game system to ever grace the market. And now the story of a wealthy game company who lost everything, and the one mob boss who had no choice but to break it all apart. It’s the Gizmondo.

The system

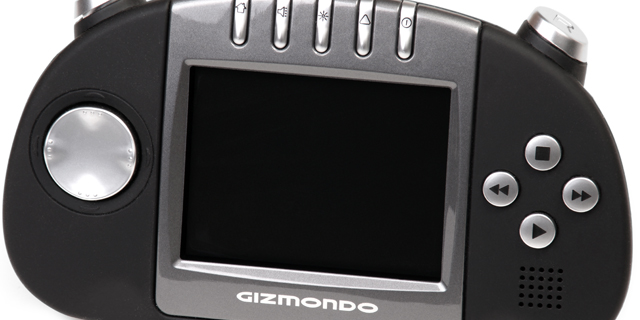

The Gizmondo was a handheld game system made by Tiger Telematics (Not to be confused with Tiger Electronics) in 2005, in an effort to compete with the Nintendo DS, PSP and Nokia N-Gage. The system itself boasted some rather-impressive hardware, including a VGA camera, cellular radio, GPS, SD card slot and more powerful specs than the PSP. Because of all this, the system was theoretically capable of nearly console-quality games, but it never came to pass. The Gizmondo’s operating system is a modified version of Windows CE, Microsoft’s minimal OS for mobile devices.

The familiar development environment of WinCE allowed the system to get some big-name developers lined up, promising to make games for it. EA was able to port SSX 3 to the Giz, and had several other titles from the EA Sports series in the works. Ubisoft supposedly had a console port of Rayman 3 in development, and Eidos was working on a Tomb Raider game. Very few of these made it out at all; in fact, the only games to ever be released in North America for the system were its launch titles. The rest of the system’s promised software library included Momma, Can I Mow the Lawn, which lent a Crazy Taxi-esque mentality to lawn mowing; Milo and the Rainbow Nasties, a flagship Giz title that would have featured gameplay not dissimilar to Super Mario Sunshine; Colors, a GTA clone; and even an unnamed augmented reality game using the rear camera.

Some other standouts from the Gizmondo’s lineup included the infamously-titled Sticky Balls, a billiards-inspired physics puzzler in which the player must knock balls into like-colored groups, whereupon they stick together. Sticky Balls ended up being the best-selling game on the system. Take that for what it’s worth. Next, there was Trailblazer, a remake of an 8-bit computer sci-fi racing game from the 1980s, and Gizmondo Motorcross 2005, a top-down motocross game developed by now-acclaimed PSN developer Housemarque.

The story

The Gizmondo itself started as something of a passion project by Tiger Telematics’ charismatic Carl Freer. The original idea to make a handheld that was secretly a child-tracking device was soon scrapped by Freer, in pursuit of creating a legitimate competitor to the longstanding champion Nintendo and new challenger Sony in the portable gaming scene. From then on, the goal was to create the most advanced, feature-rich handheld gamers’ money could buy. The buzz surrounding the system was big, thanks to its tantalizing spec list, and media and investors were quick to jump on board. So, what happened that could have dulled the hype? Well, to be honest, the legacy of the Gizmondo itself was not terribly interesting. It lasted less than a year on the market and barely made a dent in sales charts, moving less than 30,000 units in its lifetime. No, the interesting parts are the events surrounding its existence.

Stefan Eriksson, one of the two heads of the Gizmondo project (along with Carl Freer), was found to have used his connections to the Swedish Uppsala mafia to finance and produce the handheld. It all began one fateful day, when a Ferrari Enzo was found snapped in two on a California highway, with Eriksson at the wheel (according to the official police record). The car was found to have been stolen, and was being transported to his home. The police investigations that followed soon unraveled the tangled mess that was the man’s various money trails, which lead to the discovery of the scandal surrounding the Gizmondo. The huge backlash from the scandal got a good deal of industry attention, and essentially made any shred of credibility the system had going for it vanish into thin air, from investors, developers and consumers alike. With the ensuing chaos from the eventual imprisonment of one of the company’s leaders, the system was discontinued less than a year later. The icing on the cake? Upon Eriksson’s release from prison, one of the first things that was put on the table as part of his return to the business were plans for a successor to the Gizmondo.

The possibilities

The fallout from the Enzo crash is arguably the key factor in the system’s premature death, helped along by stagnant development and spending a great deal of the project’s budget on a swanky, expensive party and marketing campaign around the UK launch. Its dizzying price point of $400 for a base model system, or $229 for an ad-supported model whose advertisement service was never actually brought online before the handheld’s demise, plus mounting pressure from the DS and PSP, meant the Giz was never got the chance it deserved. If it were under more scrupulous care, it would have at least been around for longer.

The hardware itself was downright revolutionary, doing things that would be unthinkable until the smartphone boom later that decade. Early on in the project, there was even talk of the system being an all-digital platform powered by an App Store-like online marketplace to download software. Speaking of software, if the Gizmondo was going to make any sort of impact, it would have to show it could do things the PSP and DS couldn’t. The aforementioned AR demo game would have been a good start. Such a title would likely not be the number-one defining killer app, so the Giz would seriously need to flex its superior graphical muscle as well in order to succeed. The OS would also need to continue to be updated for stability, usability and, most of all, speed. A polished operating system would cement the device’s place as a portable multimedia device without resorting to a proprietary media format like the PSP’s UMDs; the SD slot is a user-friendly and smart addition.

Finally, that price would have needed to drop way, way down before any consumer would consider buying one. Maybe take out the cellular radio to shave off a few bucks and get it below $300 for the ad-free model. This would be the most important part, as the standard Giz cost more than any home console at the time, and few gamers would part with their money so quickly based on sheer technical novelty.

It’s hard to deny that the Gizmondo was never meant to succeed in any capacity other than an elaborate money-laundering scheme. In retrospect, it didn’t stand a chance against the current titans of the handheld gaming market. That said, I actually love my Gizmondo. It’s a handheld that has a lot of personality, and makes for a great conversation piece. Yes, it is deeply, tragically flawed in a laundry list of ways, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth owning, especially for collectors. If you want to have a piece of gaming history that may still be useful through the use of homebrew software and a modest-but-interesting game library, then I can at least say that the system is worth a look, if for nothing else than the ability to recount one of the most memorable train wrecks in the industry’s history.