Even the biggest name in gaming let its whimsy get the best of it, and how it managed to release one of the most confounding pieces of gaming hardware ever conceived is a bit difficult to untangle. But to understand how the Virtual Boy was ever released, you first have to understand the economic, political, and social factors of the turbulent mid-1990s that culminated in its release.

The system

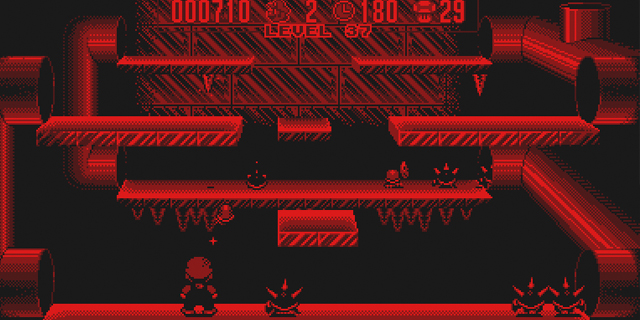

The Virtual Boy was released on July 21, 1995 in Japan, just over six years after the Japanese launch of the Game Boy. The system was not so much portable as it was self-contained; it featured a partial helmet apparatus mounted on a stand that a player would look into in order to see the game being played. The main gimmick of the system was that it could display images in stereoscopic 3D using a complex system of LEDs and mirrors, giving a convincing illusion of depth. However, given the high cost of a full array of RGB LEDs at the time, Nintendo decided to only incorporate red lights into the system’s display, restricting it to only showing different shades of red. This red-on-black 3D display was claimed by many to cause eye strain and even retinal damage, although the latter claim has been mostly unfounded.

Although it was restricted in color spectrum, the level of detail that was possible in Virtual Boy games was remarkable for the time. Sporting a 32-bit processor, it was able to push out visuals that rivaled that of the SNES. Some games even were able to use 3D polygon graphics, which were rare enough in console gaming, and downright unheard of in portable at the time. It pulled off some impressive feats with the limited tools it had, but its weaknesses proved to be far too limiting in the end.

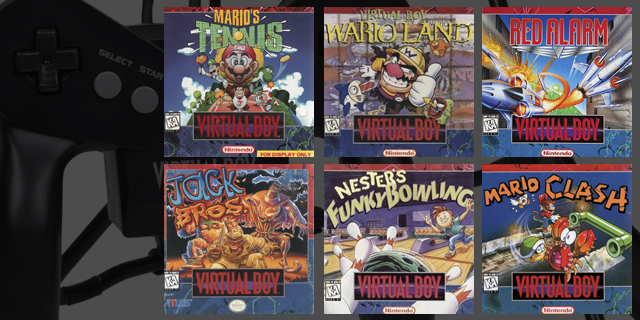

Across all territories, the Virtual Boy’s library consisted of a grand total of 22 games, only 14 of which were released in the United States. Few developers had faith in the platform, as well as in Nintendo as a whole at the time, so convincing them to take a chance on it was a difficult task. The pack-in game for the system was Mario’s Tennis. The game is a fairly basic tennis adaptation, though the depth allowed for more accurate assessment of the ball’s location. Virtual Boy Wario Land (not to be confused with Super Mario Land 3: Wario Land on the Game Boy) made a stronger case for the hardware, with levels that used the 3D of the system to make multiple planes of movement and creative puzzles.

Red Alarm was similar in many ways to a Star Fox game: the player controls a spaceship moving through corridors, shooting down enemy ships and the like. What made Red Alarm impressive was that it was not strictly on rails; it allowed the player freedom of movement in levels, though the stages themselves were linear in structure. During boss fights, the player can often fly around a room at will to pick optimal vantage points.

A lot of people don’t realize that the first game in the revered Shin Megami Tensei series released in the United States was not, in fact, an RPG. Jack Bros. was a spinoff puzzle platformer for the Virtual Boy that featured the franchise’s three mascots: Jack Frost, Jack Lantern and Jack Skelton. Beyond this distinction, the game’s low production run and even lower sales meant that Jack Bros. is now one of the rarer games in the system’s library. The game itself is a competent puzzle game that uses the 3D depth to incorporate multiple floors of a room into puzzles. It is an interesting experiment, but not worth breaking the bank over.

The story

Other than the pre-crash era of gaming, the mid-’90s were the most prolific period in terms of hardware options. Competitors came about in an attempt to wrest the console crown from Nintendo. Besides the most notable Sega, there was Atari, 3DO, Philips, NEC, SNK, Casio and even Sony (I know, crazy, right?). Moreover, during the course of the 16-bit generation, Nintendo didn’t have total domination over its key markets like it did in the previous one. Sega was putting up a good fight for market share, making it a much closer race for the winning console. NEC was also pulling in hefty profits from its PC-Engine in Japan, weakening Nintendo’s grasp further still. This meant that Nintendo had actual reason to worry about its position at the top of the gaming food chain. It would need to take some big risks and show off something special in order to regain ground.

Nintendo also had, prior to this time, been known as somewhat of a tyrant in terms of software publishing. Initially in part as a reaction to the uncontrolled Wild West of console game production of the Atari era, Nintendo exercised total control over a developer’s games if they were to be published on their hardware. Nintendo owned the code, the means of production, the distribution schedules and a large share of the profits. Heck, in the previous generation, it even kept developers from making games for competing platforms.

This policy was made more lax in the 16-bit era as Sega became a more popular alternative with consumers, but Nintendo still retained many of the same restrictions. This meant that developers were more willing to jump ship to another platform if it meant more autonomy in the production and distribution of their products. Aside from casting Nintendo in a less-than-favorable light, this was also proved to be one of the bigger nails in its coffin for the generation to come.

Finally, there was the clash with Sony. In one of the most catastrophic business deals in the company’s history, Nintendo ditched Sony as its partner for its SNES CD attachment in favor of Philips, well after Sony had already shown off the add-on. Thus, Sony went and finished development of the console by itself, creating the PlayStation. The PlayStation launched in 1994 in Japan, when Nintendo was still only just beginning to talk about its next console in the wake of the failed SNES CD. The Sega Saturn had also launched a month prior, putting pressure on Big N. With its next home console not in the cards for another two years, and the Game Boy platform entering its fifth year, Nintendo had to come up with something big and flashy in a hurry to keep consumers’ eyes and ears on the Nintendo brand. Something wild and unexpected that could do things that other platforms would only dream of.

The possibilities

There were many games under development for the Virtual Boy that were canceled upon the hardware’s discontinuation. Most notably? Titles from Rare, like Donkey Kong Country 2 and GoldenEye 007. Other canceled titles include shooter Faceball 2000, Battlezone clone 3D Tank, a Zelda-style action-adventure titled Dragon Hopper and VB Mario Land, which would have marked Mario’s first true platformer on the system. The Virtual Boy’s homebrew development scene is still relatively active, releasing such impressive projects as a FPS game engine, ports of Super Mario Kart and Street Fighter II and various tech demos.

Nintendo’s big gamble on 3D graphics and games was a massive failure. The Virtual Boy was discontinued six months and one day after its release in Japan, and is frequently regarded as a punchline. It proved that even the mighty Nintendo can make mistakes, and that sometimes big risks simply don’t pay off, no matter who you are. While it is impossible to regard the Virtual Boy as anything but a failure, the system is still one of the best conversation pieces in game hardware. Its bizarre design evokes curiosity, and draws people in to at least give it a try. Moreover, the system showed Nintendo’s interest in 3D gaming, which it attempted to get off the ground several times over the course of the next decade or two, culminating in the release of the 3DS. If nothing else, the Virtual Boy is a curious footnote in Nintendo’s history, and we’ll always remember it as the time that a titan stumbled.