There are a few isolated moments amongst thousands that are easily recalled when contemplating growing up. Paying your own dentist bill. Buying a house. Being responsible for more than just yourself. Often they come out of nowhere, requiring on-the-spot common sense and a lingering afterthought of “gosh, I hope I did that right.” We as gamers face common challenges when we mature; social pressures to play less, other hobbies, relationships and work all can disrupt a good game session. Sometimes they should. But beyond that, do we still feel the same when we play games as we get older? No doubt we are wiser, and probably harder to impress, but do we still enjoy them as much? Do we enjoy them the same way?

My sobering moment happened on October 30, 2011, almost a year ago today. It was a moment that I will remember for the rest of my life, but might seem very insignificant to somebody who doesn’t know, or understand, video games. I was playing through the campaign of Battlefield 3. “A-ha!,” you shout. I know what you’re going to say. You played through the single-player portion of Battlefield 3, something nobody in their right mind does.

Not quite. It occurred during the second-to-last chapter. I was running up a hill and hid behind some cover. I popped out and shot an enemy in the head. Normally, a player would smile at this act; a headshot usually means a one-hit kill and negating the threat. But something hit me at the moment.

I wasn’t even sure what it was at first; was I not enjoying myself? Was the single player campaign weak? Was I bored? No. I started to feel bad about killing the enemy.

The guy you killed isn’t even real. You didn’t kill anybody. It’s a game, a fantasy re-creation for our amusement. Anything you feel is just reading into it too much.

That’s what I tried to tell myself after I beat the campaign. It didn’t happen in any of the other levels, and it didn’t happen afterward either. I passed all the chapters and moved on to the excellent multiplayer.

It’s a weird feeling. Why did I yell at my spouse? I care about them, I love them… why did I get so angry? Am I doing the right thing? Do I have the right job, living situation or partner? But to question a hobby is even stranger. It’s no less intimate. Do I still enjoy playing video games? If so, why? Am I changing as a person, maturing, and is that sinking into my opinion of games?

So many questions, but do the answers lie within another game? After replaying the same chapter a few days ago, the feeling wasn’t there. Maybe my awareness of how I felt the first time shielded me. I know these are digital re-creations, lines of code. Nothing more. But a small sense of guilt had crept into my conscious thought. Should I enjoy consequence-free, fictional murder?

It’s a strange example of a game to use; Battlefield 3‘s campaign wasn’t touched upon much by writers, and rightfully so. The storyline isn’t very deep, and it’s clearly overshadowed by the multiplayer. A better example would come this summer, when I played a third-person shooter called Spec Ops: The Line. What a terrible, generic title. Was it part of a series? I didn’t care, and didn’t have any interest in the game until I heard that Spec Ops: The Line was something totally different. It made you question shooting and killing.

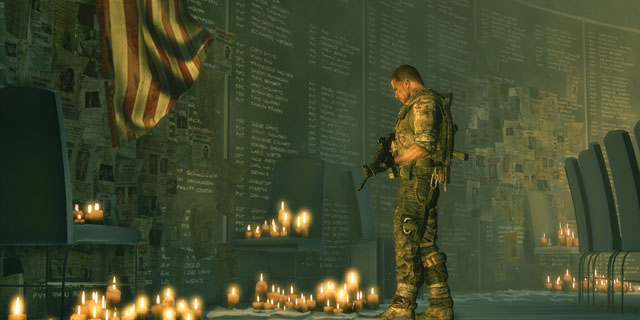

Spec Ops: The Line is a military shooter. You play as Walker, in charge of two allies as you march into the city of Dubai. The setting is unique, as the city has been half buried by a massive sandstorm. Another portion of the military had been brought in to try and evacuate the citizens. Something had gone very wrong. It’s up to you to infiltrate the city and find out what happened and evacuate the survivors.

Okay, sounding good so far. There’s a cover system, and modern graphics that look good enough. It’s a fairly standard third-person shooter, with a few additions to gameplay that work (sometimes). You can order your two squad members to perform cover fire, launch grenades and other helpful tricks and tactics. Rogue enemies ambush you in the desert outside the city, and you fight back. Voice acting is excellent. I still saw no difference between this and the hundreds of military shooters available.

The main character of the game, Walker, soon becomes the focal point of the story. After the first few levels, you learn that the regiment in charge of evacuating the Dubai civilians, the 33rd, failed. Returning to the city, they attempted to set up martial law to regain some order. Atrocities were committed. Many of the 33rd didn’t like this and lashed back. So, small civil war in an impossible city in the middle of the desert, surrounded by the mystery of what actually happened. A hidden DJ provides color commentary to Walker and company. Did I mention the leader of the 33rd, Konrad, once saved Walker’s life?

You have a lot of elements here. It’s much more dense and original than most shooters. This is exactly what the first few chapters of any game should do; establish the setting, mood and mystery all in one. And business was about to pick up. A mistake occurs, and a firefight ensues. You end up killing fellow American soldiers.

That’s a weird sentence to type. You don’t see that very often in games. American soldiers as the bad guys? Hovering over them with your mouse even produces a different color than the other enemies.

Your teammates are not happy. They didn’t sign up for killing American soldiers. Insurgents and terrorists are one thing, but U.S. troops? For the rest of the game, the tension is heightened by angry dialogue, highlighting the mistrust brewing. Walker barks orders, but Lugo and Adams become more and more reluctant with each passing battle. They begin to condemn Walker for forcing them into the situation. There’s dissension among the ranks. You’re affected by this dialogue, because we like all three characters, and we identify with Walker. Did he make the right decision?

They approach an area called the Gate. Against Lugo’s wishes, Walker decides to use White Phosphorus rounds against the 33rd soldiers, a particularly nasty chemical weapon. (Not the typical actions of a video game hero.) The attack is successful, but to a degree Walker did not foresee. It turned out that the 33rd had been housing civilians for safety. In a shocking scene, you are forced to march through the area, as both civilians and 33rd troops reach out to nobody in particular for help. As one of the loading screen messages says, this is your fault. Innocent civilians, dead. The exact opposite of what you were trying to do. And they all died horribly. It is a punch to the gut; an emotionally crippling scene. It’s also morbidly brilliant.

The story takes many twists and turns, but you start to condemn the whole situation. Hate it, even. You don’t feel good about killing soldier after soldier. The White Phosphorus incident won’t get out of your head. Walker’s attitude changes. He screams at fallen enemies in anger. He’s frustrated and frightened when reloading his weapon. Lugo and Adams, to their credit, stick by his side, but only because he’s their superior. This brings up another slew of moral questions about loyalty, following orders, obeying the chain of command and survival.

Deep. The story has layers. It is morally ambiguous. It is philosophical. The head writer has his own belief of what the entire story is about, but also says that it’s open to interpretation; my favorite kind of story.

One of the strongest “choice” scenarios comes late in the game. It was the scene that affected me the most, one that I will always remember. One of your allies is taken by a lynch mob, screaming for help. You can hear him choking. Horrified, you turn the corner to see him hanged. You shoot the rope and try to resuscitate him. Dead. The crowd hovers. You get the notion they want you dead too. Aren’t they justified? Haven’t you killed their loved ones and fellow citizens in an equally savage act?

Control switches to you and in a nail-biting, no-blink, sweaty-palms moment, you have to choose. The game doesn’t prompt you with a specific set of choices either. Your ally screams at you for an order. Do you open fire? These are civilians… but they killed your friend… but you’ve already killed many of their kind in cold blood… but you want to survive. They’re moving closer. What do you do?

Whatever choice you make, you will be full of adrenaline, guaranteed. Few shooters have made me feel this way; did I enjoy the graphics, setting and fresh take on a tired genre? Or was I in small shock over the awful choices Walker made, with me at the helm? Was it exploitation? Was it too preachy?

Those who are critical of the game will point to holes in the story, or that the immersion was broken too many times to get fully committed to finishing the game. For me, it was an unforgettable experience. There’s a reason Spec Ops: The Line has garnered a ton of attention and discussion. Far more than what a “generic” shooter should get.

After beating the game, reading about it, thinking about it and writing about it, I realize that the title isn’t so terrible; it fits. The Line. Did you cross it? How did you feel about it? Not just about Walker, Lugo and Adams and their decisions. You, specifically. Do you feel bad about a game designed to reward murder? Do you feel bad about enjoying it? Or can you completely detach yourself from that aspect and just enjoy the challenge? It’s entirely possible I’m reading too much into this, but I know I’m not alone. The designers of the game had a very specific goal in mind when making Spec Ops: The Line. They didn’t set out to make just a generic shooter where you kill thousands of mindless enemies. Far from it, they built the game around the story and wanted to encourage discussion about the shooter genre.

It also creates a bit of a paradox; how can a game that essentially rewards you for shooting enemies (to progress through the story) be a critique of the genre?

I always appreciate it when games try something new. An evolutionary or revolutionary game mechanic doesn’t always yield successful results; Spec Ops: The Line sold approximately 600,000 units to date. Hardly Call of Duty numbers. But it attempted to do something new and get people talking. To get people thinking. And, the goal of video games, to get people feeling.

I’m not sure if I feel “bad” about shooters, or enjoying them. But I am sure that I’m pleased to have played through Spec Ops: The Line, and would love to see other developers take this risk. Even if it means more sobering moments for me, making me feel uncomfortable about enjoying shooting people in games. I look forward to it and, after much contemplation, don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing. But I won’t stop playing them just yet; some still yield spectacular experiences, and I would never say I regret my time playing Battlefield 3 or Spec Ops: The Line.