At Snackbar Games, we spend a lot of time discussing core mechanics. Visuals, presentation, audio and gameplay are common topics we cover. However, more detailed analysis will yield our thoughts on the game’s longevity, emotional connection, progression, use of tech, multiplayer and a slew of other facets, providing an indication of a game’s quality relative to our experiences. Sounds pretty simple, right?

Sometimes a game has extraneous factors that not only impact sales (check out Graham’s article on Advance Wars), but also player enjoyment and general reception. In certain cases, this is entirely unfair. Shouldn’t a game be judged solely on what it is, instead of some weird, irrelevant reason? Unfortunately, nothing exists in a bubble and games are no different. Personally, I’m overly harsh towards some games due to the price point.

Guild Wars 2 is a prime example. It’s not a bad game by any means; in fact, I put it at number eight on my top ten list of 2012. I was Percy Norntinker, a nerdy-looking engineer who used guns and gizmos to overcome the foes inhabiting the world of Tyria. The game could be described as a single-player MMO, which sounds impossible… until you play the game and understand.

The storyline is more responsive to player actions: there’s a progressive “world-versus-world” battle players can drop in and out of, and there are enough items to collect, enemies to destroy and environments to explore to keep you entertained for months. So what gives?

Guild Wars 2 was one of the few games I didn’t get my money’s worth playing, and it’s entirely my fault. I bought the game at full price, on a whim, without doing much research or figuring out if any of my friends were going to play. Despite it having a large focus on the single-player aspect, games of this nature are always more fun to play with a buddy or two. I had a single friend who played regularly, but we somehow ended up on different servers. That was the end of Percy Norntinker’s adventures: level 37, 15-percent world completion. Viewing the game from a critical standpoint, I really enjoyed it. On a personal level, I felt empty.

If I had spent $25 or $30 on it, I would have considered it a fine experience. But I bought it at launch – $59.99 plus tax – and I wasn’t exactly rolling in money at the time. I didn’t necessarily feel cheated, but my experience was soured. Is it fair to the game? Absolutely not. Yet my feelings linger and I begin to think of opposing examples, wherein my experience was enhanced due to the price point.

The Orange Box is lauded as one of the greatest deals in video game history. It was a compilation of Half-Life 2, Half-Life 2: Episode One, Half-Life 2: Episode Two, Portal and Team Fortress 2. Today, its price varies from $20 to $40 depending on the system. Not only was this the launching pad for the surprise hit Portal, but you could argue each one of the games alone is worth the price. Instead, you got all five.

Nearly every review of The Orange Box mentioned the pricing; it was a major selling point. This was obviously due to it being a collection of (mostly) previously released games, but it helped entice people to buy and enjoy the games when they may not have otherwise. They’re the exact same games, but the pricing makes them much more. Would the reviews have been as strong if the collection were $100?

The phrase “free-to-play” used to be taboo, but as of late, there have been a few shining examples of how a free game can compete with full-priced ones. Dota 2 is an unquestionably great value; it’s completely free save for aesthetic outfits, couriers and items you can purchase (which don’t affect the balance). I’ve played nearly 900 hours and haven’t spent a dime. It’s absolutely one of my favorite games ever, and the fact that it’s free puts the proverbial cherry on the ancient.

Hearthstone is a free-to-play game by Blizzard that continues to buck the stigma. It’s well-designed, if strange. A World of Warcraft-themed card game sounds gimmicky and lame, yet Blizzard side-stepped all the preemptive complaints I had. It’s fun, it’s addictive, the cards look great and each has its own sound effect and personality. Even more surprising, the magic and ability animations are a treat to view, even after repeated viewings.

Like Guild Wars 2, I didn’t play a lot of it. I practiced against AI and a few humans, but barely dented the surface. I wouldn’t rate it as high as Guild Wars 2, but I didn’t have the same buyer’s remorse. I didn’t feel guilty at all about putting my deck of Orcs and Murlocs away and moving on to a different game. No financial investment? No problem.

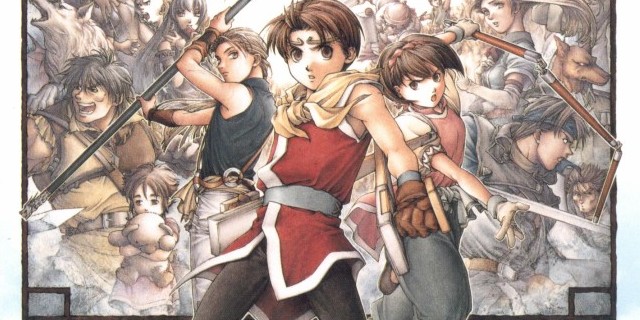

Video games have a weird flow. New technology can render them obsolete, they have a strong nostalgic connection and don’t always go down in price with time. Some classic games, particularly limited-release RPGs, are stubbornly expensive to this date. Suikoden 2, a fantastic JRPG, fetches a minimum price of $150 among retailers due to a lack of updated releases for the North American market. Is it worth the outrageous cost? Will opinions suffer due to the lack of exposure, or offense at the cost?

Undoubtedly, and it’s not Suikoden 2’s fault. It’s the same game, whether you play it for free or 150 beans. Pricing creates a strange situation. It can cause negative feelings, such as buyer’s remorse, or having unfairly high expectations about the product. Prices are all over the place and the only real solution is research. Read reviews, find out if your friends are going to play it and see what the company’s history is on price drops and sales in the future. If you’re on the fence about a game, it’s always good to err on the side of cheap.