Lev Grossman is one of my favorite authors. The first two books in his Magicians trilogy, The Magicians and The Magician King, are right up my alley. They’re Narnia meets Harry Potter with a macabre twist. The series is scary, realistic in its own way and has a protagonist whose voice matches my own at times. It really does feel like it was written for guys just like me; obsessed with fantasy and not exactly sure what to do in life. The third book was released recently, The Magician’s Land, and it, too, was spectacular. Some scenes were so beautifully written that I will never forget them. But something wasn’t quite the same.

The dark, foreboding tone was there at times. The first two books relied on the notion that magic was a blessing, but also a curse, and extremely dangerous if put in the wrong hands. Two parts in particular, one chapter in each book, shook me. I’m so rarely so affected emotionally by books that this was a disruptive surprise. No such chapter existed in the third book. I was surprised to find out the ending was… happy? Everybody wasn’t killed? No gruesome attack by a monster? Huh.

I’m not complaining; it was just surprising. I did a little research on the author and found out Grossman admitted to being clinically depressed while writing the first two books, but then received help and was in a much better state of mind for the third. I was thrilled to read he was better, but also saddened he wrote the first part of the trilogy in a dark state of mind. Saddened, but also appreciative. His personality, for better or worse, showed itself in the fiction. Story details, character motivations and plot were at the mercy of his emotions. It all of a sudden made a lot more sense as to why the tone shifted in the third book.

I thought of this topic while doing another type of research: playing old-school games. My goal was to start at the year 1985 and try to play a big-name title of each of the following years. I decided upon Gradius for 1985 and Castlevania for 1986. (I know the years are a bit weird with arcade ports and Japanese release dates, but bear with me.)

Playing old games is an exercise in patience and appreciation. It’s impossible to compare them to modern games in almost every area of game criticism. You can’t complain about the visuals, the technology available to them was about 30 years older than the hardware we enjoy today. The same goes for the audio. Games were still a relatively new medium, so common principles like presentation and even end credits weren’t given a standardized level of quality. But one facet does remain constant: the atmosphere and tone of a game. And, much like the Magician novels, it has to do with the creator’s personalities seeping through the cracks and showing themselves in interesting ways.

The first Gradius doesn’t quite hold the “classic” title. Like most NES games, it’s too short, too difficult and too archaic to hold up to today’s shooters. But some unique features still make it worth a quick play. The weapons bar and upgrade system still work really well as a risk-reward function. Essentially, the more upgrades you pick up, the more powerful weapon you get. The trick is, once you activate the power-up, your bar resets to zero. Can I survive five or six upgrades without dying? Or do I use them immediately, then save up with the additional firepower? It’s uncomplicated and surprising that such a feature was implemented in a game nearly as old as I am.

Level three had me banging my head against a wall. It’s filled with Moai statue heads from Easter Island (in space, of course), shooting endless bubble rings at you. Unless you have a shield, take one hit and you’re dead. It is maniacal in difficulty, but also endearing. It’s very rewarding when you beat the level. But there’s no real reason given why rock head ares in space throwing bubbles at me, but there doesn’t need to be. The designers of Gradius thought they looked interesting enough, and enough of a contrast to other enemy types, that they would stand out and appeal to players. They were right.

This sort of decision wouldn’t fly with today’s games, no no. Everything needs to make sense and have a purpose. Here, the creators of the level just decided they looked cool. It turned into a series tradition, with all sorts of Moai statue heads appearing in nearly every Gradius title after. I’m terrified to learn that in future games, the heads turn around and keep firing at you once you’ve passed them. It’s not my cup of tea, but nice to know somebody’s personality manifested itself in a creative way and has lasted generations. As of now, there are 18 different type of Moai enemies in Gradius games.

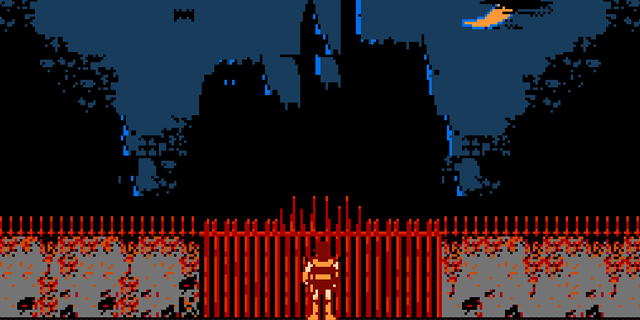

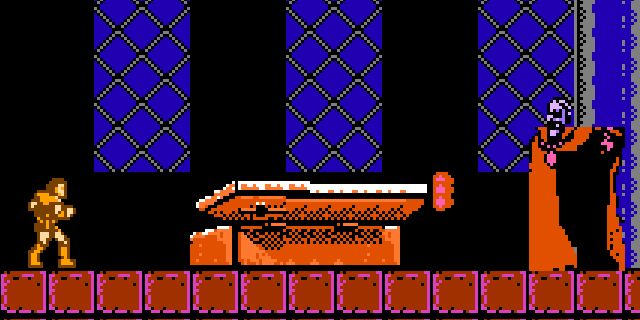

Castlevania, on the other hand, does hold the “classic” title, and is a masterpiece mainly for how it feels. It still retains the trademark Castlevania atmosphere. Enemies of all types of horror, from mummies to Dracula, are present. Despite the level design being puzzling at times (remember, this was 30 years ago), there’s a ton of personality. Gothic architecture dominates the world. Each level is dark, but doesn’t sacrifice our ability to see due to lighting tricks. It’s all color use and art design, and it’s remarkable that it still holds up.

One of the best parts of the game, one where emotions from an individual seep through, is the soundtrack. Many of the tracks, particularly “Vampire Killer” and “Wicked Child,” remain some of the best melodies ever created for a video game, and the songs have remained in Castlevania lore to this day. Unusual for the time: the soundtrack was composed by a woman, Kinuyo Yamashita. Even today, most video game compositions are dominated by men. It was no fluke, as Yamashita went on to compose for over 40 different games in her career.

Remarkably, Castlevania was her first composition job, and remains one of the best soundtracks on the NES. The fact that the haunting atmosphere of Castlevania, much of the reason it was so successful, is due to melodies created on restrictive hardware is a miracle. The fact that Yamashita (along with her co-worker Satoe Terashima) created this work of art at age 20, with very little musical experience, is astonishing. Millions have Konami to thank for allowing her to express her budding musical talent on such a (soon-to-be) grand stage.

One of the complaints about AAA games, along with launch problems, is that they lack personality. They feel manufactured, catering to the masses and only caring about the almighty dollar. Part of the problem is that modern games require a staff of hundreds, or thousands. How easily can one creator’s personality shine through? All aspects of the game’s design are put through the ringer, with deadlines and approvals, perhaps leaving less room for individual creative tone.

Part of the reason indie games have had so much success, I believe, is the full feeling of personality when playing them. Most of them are made by a handful of people, a small crew with a vision. One that’s easily implemented, as they’re not concerned with the most updated graphics or hardware, but a message. The message may come through story or graphics, audio or mechanics, but it’s there. Some games are just dripping in atmosphere and style – Limbo, Braid and Transistor to name a few. Ask the developers of those games what they wanted to bring to the table, and I guarantee you their answers will be fascinating and aspects of the game will be a window to their emotions.