Most games have a clear set of goals in mind for the user to experience. This usually involves completing the game’s main campaign; starting a new game, going through levels and defeating the end boss. Roll the credits. You can now discuss what you thought of the ending with fellow players, or start a discussion on the game’s themes without feeling left in the dark.

Some of the more interesting experiences come from when players go off the beaten path. They ignore the checklist given to them by the developers. Maybe they go for every achievement, or try to play with a heavy handicap, or try something nobody in the world has yet. It is this dedication to mastery that I find so fascinating. To apply time, practice and discipline necessary to master a game means there’s a deeper connection and a more personal attachment. Why does this happen?

You can’t attempt to master a game without some level of enjoyment. It takes a special game to entice someone to drop everything else and focus on only it. It needs to have the player call out to the game, pleading for it not to be over.

Sure, you may have beaten the game. But did you beat the game on the hardest difficulty? Now how about without using items? Or losing a single life? All of a sudden, the game changes, not just in the amount of enemies’ health, but also in your approach to the game. Your way of thinking and playing must be fluid and flexible. Your learning and understanding of the game’s mechanics must be memorized, so that playing becomes as natural as breathing.

Mastering anything, from plumbing to painting, is a long, difficult road. They say it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill; that’s a lot of games of Chess. The road to mastery is filled with pain. In game language, that means a lot of dying and frustration. With it, however, comes the highest level of satisfaction, and it’s all the more important because there are so few who choose to follow that path.

There are very few games in which I would call myself a master; true masters will find fault in my pursuit, play style and result. But the dedication, planning and satisfaction I achieved while playing Ikaruga is probably the closest I ever came to reaching that hallowed ground.

Ikaruga is a Treasure-developed top-down shooter, initially made for arcades and Dreamcast in Japan, reaching the West in 2003 on the GameCube and recently re-released on Xbox Live Arcade. It had the old-school mechanics of arcade shooters you found in the ’80s, combined with an updated engine, gorgeous visuals and a design that strays dangerously close to perfection.

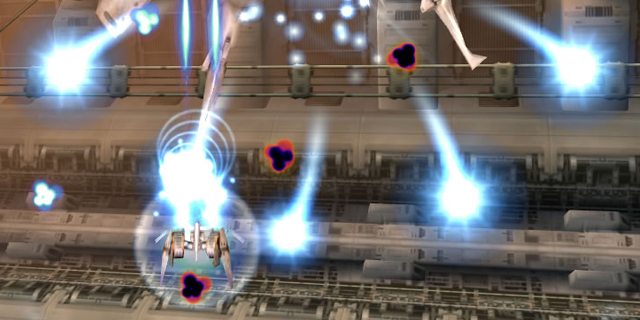

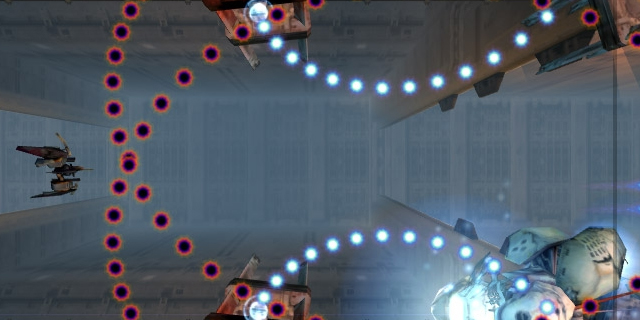

There are no power-ups. You can fire, of course, but the meat of the game comes from your ship’s ability to switch colors at the touch of a button. The transformation of polarities is instant: black to white, to black, and so on. While you’re a white ship, you absorb white enemy fire and do more damage to black enemies. While you’re a black ship, you absorb black enemy fire and do more damage to white enemies. Hit a wall or an enemy and you die. A small bar on the bottom left shows how much fire you’ve absorbed. By pressing the R button, you release that energy in a homing-fire attack.

The scoring system is brilliant; for each kill you rack up in threes of the same color, you build up a chain score. It doesn’t matter the order of colored enemies you kill, just that you do it in threes. So white-white-white, black-black-black? Okay. White-white-white, white-black-white? No. Your score counter will reset to 0 and you have to build up the chains again. Once you hit eight chains, you reach “max chain” for every three enemies you kill, earning massive points and earning extra lives. Since you don’t start out with many, this is crucial to making it to the end of the game. Therein lies one of the many layers of Ikaruga: do you go the safe route and just blast everything in sight? Or do you try to rack up points for prestige, better rankings and extra lives?

Each of the five levels are filled with black and white enemies, and the screen is often covered with waves of bullets. There are no random patterns; they always show up in the same manner, speed and routes. Depending on how well you do and how quickly you eliminate them, extra enemies might show up for a chance at a higher score.

A good player can beat Ikaruga in about half an hour. There are multiple modes of difficulty, and you can adjust how many lives you have. The longer you play the game, the more continues and lives you can use. If you stick with it, there’s a very good chance you’re going to defeat the end boss eventually and see the end credits. But where’s the fun in that?

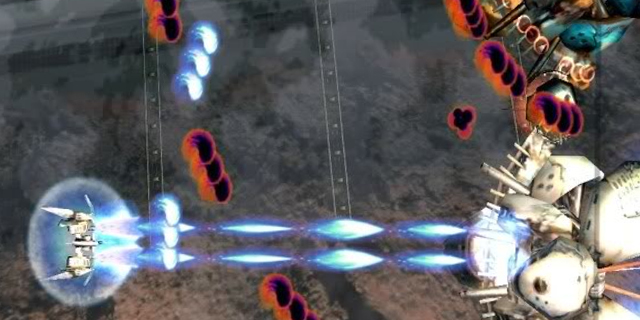

After beating Ikaruga ten times or so, I wanted to jump up to the hardest difficulty. On this mode, when you destroy enemies, a blast of white or black bullets emerge and head towards you. This is both a blessing and a curse. An optimist would perceive this as extra ammo for the homing missile attack. The rational, reasonable person would take one look and say “are you kidding me?”

There are multiple ways to master Ikaruga. Go for the elusive S++ ranking in each level? Try the “bullet eater” technique? Complete the game without firing a single shot, and just absorb enemy fire the entire time? (Bosses, obviously confused by your pacifist nature, will eventually fly off.)

I had to be realistic. I wasn’t a cyborg, so I wasn’t going to go for the highest rank. I was in college, so that gave me some excuse to not dedicate my entire life to the game. But I did want to push myself and face the challenge of beating the game, on hard mode, without using a continue. For master players, this is a joke, and that is terrifying.

First step: memorization. I’ve always been good at it, as being an actor gives me a lot of practice with memorizing lines. It wasn’t enough to go through the game blasting everything in sight; I would need to maximize my score in the first three levels in order to survive the onslaught of level four (Ikaruga‘s best) and the gauntlet of level five. This meant I had to know the levels inside and out. Where did the enemies come in and when? How many of them? Where do I shoot, when do I use my homing missiles and where do I go on the screen that will reduce the risk of me falling victim to an attack? They don’t call this genre “bullet hell” for nothing.

I remember sitting in my Calculus class, not paying any attention whatsoever. Related rates never made sense to me, but enemy and color patterns sure did. I would doodle in my notebook the enemy waves and then rush back to my dorm and see if I was right.

It’s one thing to set out a plan, and another thing entirely to put it in motion. Any skill I thought I had accumulated disappeared the minute I started up my new journey. I would die in places I thought weren’t challenging at all. I started fighting the controller, instead of welcoming it like an old friend. Patterns weren’t as easy to learn as I predicted, and my timing never felt right. The dorm I lived in was full of young, enthusiastic, wonderful people who would stare wide-eyed at the screen, asking what was going on, who I was and how anybody could beat this. I never had answers for them, but I appreciated the confirmation that this was nigh-impossible. I wanted to beat the game to impress my friends, but more to impress myself. I wanted to see what I could do if I dedicated myself to a difficult task. Many times before, I would give up if presented this kind of opportunity. Not this time.

I began experimenting. What kind of background music did I have playing in my room while playing the game? Should I have any background music? Should I mute the game’s music entirely? Play soundless? Have an audience? Lock my door and play in the dark? No variable was left untried. I kept track of my scores while under certain conditions. (I can tell you right now that playing drunk with people talking in the same room is a good way to die quickly in Ikaruga.)

I played best when of sound mind, after an hour of warm up, with rock playing in the background. Quiet songs bothered me, and heavy metal was too much. I always perform better with a crowd, so I found that a few friends watching was a good way to put more pressure on me.

With my optimal environment and more experience, I found myself breezing through the first few levels. There wasn’t any effort needed in memorizing the patterns anymore; a deeper level of knowing comes with mastery. I didn’t need to think about how I needed to swerve left and switch polarities when the boss swooped in; I just did it. Muscle memory took over, and the only physical effort I needed to exert was to remind myself to blink.

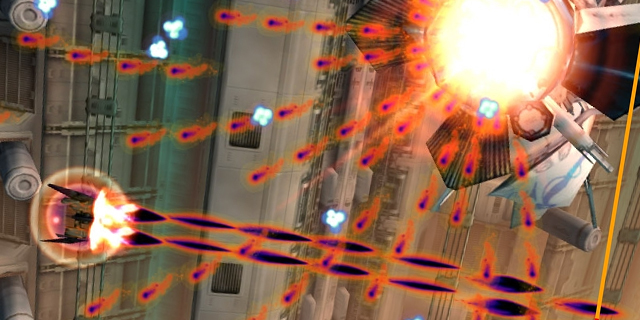

Then I hit level four.

Rage would often come into play. Building chains usually took a lot of luck and nimble maneuvering to achieve; the instinct to blast anything and everything is a hard one to suppress, but a good way to ruin one’s score and remove any hope of getting extra lives. When I would ruin my chain, I would curse loudly and often die right after. Patience was a virtue I had not obtained through hundreds of playthroughs. I started hating the game, and all it took was a few quick deaths for the controller to be thrown and the game machine to be turned off, accompanied by multiple expletives that would shock my mother and make my grandmother faint.

I quit several times per day, giving up the project entirely. I kept coming back to it, with less pressure on myself. It became less a goal and more a habit. When I finally beat the game, with three lives remaining, there wasn’t any anger at the game or a triumphant, sporadic cheer. I closed my eyes, put my controller down, and listened to the end credits music.

Life is a lot more difficult to master than a video game. We like to think that life gets easier; with each new experience, we are better equipped to handle disastrous situations, or how to take care of ourselves. With each passing day, we believe we are one step closer to knowing ourselves completely. We can take an objective snapshot and tell ourselves that we’re good at this and not good at that. That we don’t like how we handled that certain situation three years ago. That next time we’ll do better. That if we break our chain in level three at this part, we’ll know when to start building it again.

Mastering a task confirms our ability to overcome obstacles. I beat Ikaruga on hard with no continues; that means I can go on this roller coaster and not be scared. It means I can be relaxed and calm around dogs. It means that if I fail at something in life, it’s not because I’m not good enough or don’t have the knowledge, skill or experience necessary to overcome it: it’s because I didn’t have the will to see it through. It’s so much easier to accept, whether it’s true or not. Even if it’s a lie, even if I fail at something important in life like career, relationships or family, I know that I beat Ikaruga on hard mode with no continues.