It’s impossible to say with 100% certainty what kind of legacy The Last of Us will leave. But that’s easy to say, since almost nothing is 100% certain. Well, except death, taxes and obscenities screamed during a Dota 2 match. The Last of Us, an obvious candidate for Game of the Year and one of the PS3’s best, has been host to many claims. I’ve heard that it signifies that games have grown up. I’ve heard that it’s the game version of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Of Citizen Kane or Pulp Fiction. Many games have been lauded as timeless classics when they first come out, but very few stand the test of time.

There’s no denying that The Last of Us is a good game. It’s critically acclaimed, and has sold millions. It’s getting people talking. Naughty Dog has maintained its status as one of the best developers in the business. If you’ve listened to podcasts, read reviews or watched videos, you know that the game is incredibly violent. You know the characters are relatable and deep. You know that the setting is a post-pandemic world, that the visuals are outstanding and that the story and ending aren’t cliche ridden. You know that the cut scenes are professionally done and are incredibly intense, even for the most experienced gamers.

I don’t know everything about The Last of Us, or how much it will influence future games. Once again, we’re nearing this console generation’s end. It’s almost time to get off the HD train and greet…what? In the past, we knew that going from NES to SNES meant 8-bit to 16-bit. We knew that going into the N64 and PlayStation circus tents meant a leap of excited faith into 3D. This last generation was known for online connectivity, cloud servers, HD graphics, the biggest online community yet and the emergence of indie games, among other notable successes. What I do know is that The Last of Us was a gaming experience that evoked enough emotion out of me to talk about it and to want to discuss it with others.

I also know that I can’t admit that the feelings were necessarily good, or happy. It’s impossible for me to tell you that I “enjoyed” The Last of Us. I had to keep playing, sure. I admired many aspects of the game, particularly how quickly the visual contrast shifted from stunning beauty to horrifying, cringe-inducing brutality. What struck me the most was how detailed the world was. The Last of Us has a staggering amount of environmental stuff to show the player that, yes, this was a country once lived in. We’re not just saying it’s a post-apocalyptic world, we’re showing you. I’ve never seen anything like it.

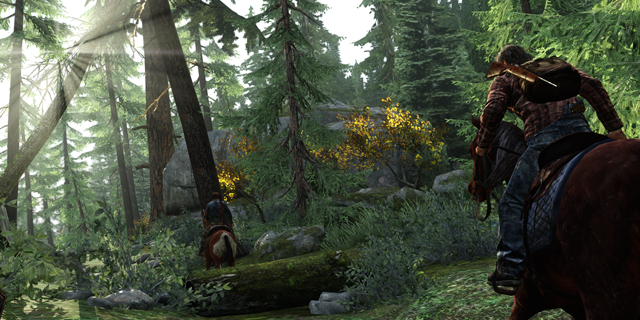

You play as Joel, a rough man with conflicting morals, trying to survive 20 years after the initial breakout that caused millions to die (including Joel’s daughter in a heart wrenching introduction), and others to turn into raging psychopaths at the hands of strange plant spores. You’re given the task of escorting Ellie, a young girl who might be the cure for the infection, across America to the Fireflies, a group of rebels who are fighting back against the martial law. The gameplay achieves the rare feat of matching the story; you’re a scavenger and vulnerable, as each fight reminds you. You’re not a one-man army, many of the infected will kill you in one hit and ammunition is anything but plentiful. Battles are akin to puzzles, as there are many ways around each encounter, but you better abandon all hope if you plan to run-and-gun. A combination of stealth, ambushes and pinpoint accuracy is a much better plan.

In each area you go through a wide variety of buildings, and it is here where my admiration for The Last of Us goes through the bombed-out roof. None of the buildings look the same. Even if they’re on the same block, or of the same make, one will have a crumbled staircase, faded bricks or different windows broken. This makes total sense. Most buildings you walk through in a city aren’t exactly the same. You don’t see row after row of identical buildings, save for a color variation. It makes total sense, except that in most other games, this isn’t the case. Call it laziness, budget restraints or a design choice, but most environments you play through have identical areas. The Last of Us can have more detail in a single house than most games have altogether.

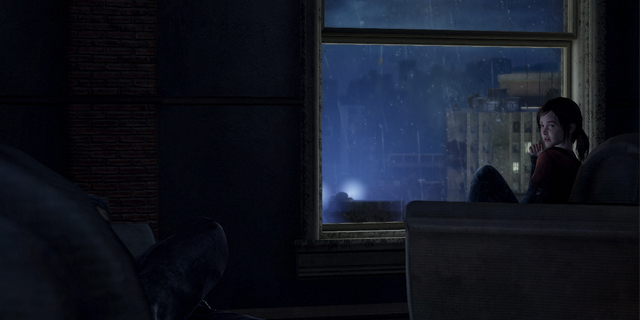

It’s the little things. Each room has an item that makes sense. We’ve all run through office buildings in our time playing games. We’ve seen desks. We’ve seen computers. But in The Last of Us, you see more. You see children’s stick-figure drawings tacked up next to the computer monitors. You see whiteboards with information on it. You see rolodexes, lamps and clocks. Each has their own variation, and no desk has a twin. Mouses and mousepads! I’ve never been more excited and filled with awe to see such common computer items in a game. Boardroom meetings have coffee containers in the back, with cups and napkins strewn about. The bathrooms have soap dispensers and hand dryers. The setting becomes as much a character as Joel and Ellie. Each insignificant-seeming object reminds us more and more of how it used to be. Or how we wish it still was.

It’s sobering. To walk through all these houses and see evidence of life once lived and now gone is depressing. The game lays it on heavily. I also found myself asking questions. Why didn’t the people in this house take their toaster in the kitchen? Are these chairs and couches just going to stay here forever? Why am I asking myself hypothetical questions about household furniture?

The game gives you plenty of time to reflect, amongst the piles of garbage and mildew. Some of the best parts involve Joel and Ellie walking through abandoned cities and bantering back and forth. Joel knows of the world that once was, but Ellie doesn’t. She asks about an ice cream truck and can’t believe what it was used for. You stumble upon a movie poster and strike up a conversation. As a player, you want to explore absolutely everything to see if you can engage Ellie in another conversation, or just to see what else Naughty Dog has cooked up.

I had to make notes about all the details I noticed, or there’s no way I could’ve remembered half of them. There were cheesy paintings in hotels, moss on brick walls, different kinds of soda in the vending machines and shirts hung up in closets. Photo frames in a kid’s room have funny pictures on them, books and DVDs have actual covers and names on them, leaves and garbage float on water and grass grows on top of a submerged car. The list goes on and on and on.

Cinematics aren’t exempt from excellence either. You meet up with a fellow named Henry and go to sit down to chat. When they sit down, the chairs make different noises. That blew me away. Nobody would’ve criticized Naughty Dog for not including sound effects of specific chairs. That’s Comic Book Guy-esque stuff from The Simpsons. But it included it, and I noticed. I’m sure many others did too. How many hours did the developers spend creating all these minute details?

Whatever the count was, it was worth it. Going forward, I’ll have a hard time accepting a digital world if it doesn’t include the level of detail found in The Last of Us. The University section in particular struck a chord with me. It nailed every aspect of dorm life: pool tables, messy kitchens, rooms with more clothes that can fit in the dresser, mini-fridges with microwaves on top and an unnecessary amount of posters. Naughty Dog did its research. It’s precisely what a dorm room looks like. If any future developers want to use dorms as a setting, this is your blueprint.

I’m not in a hurry to go back. The game offers many options for replay value; a multiplayer option exists, but I didn’t partake. You can start a New Game+, playing through the story again but keeping all your upgrades. There are numerous difficulties, including Survivor Mode which makes supplies even more scarce and removes your ability to hear enemies. Naughty Dog did well to entice you back.

But I don’t want to go back. Maybe ever. Grave of the Fireflies is an incredible movie, but I never want to see it again. Once was enough. Playing The Last of Us is draining. The battles are frantic and chaotic. You will die many times. Most of the big moments in the game are due to sudden, shocking acts of violence, and I couldn’t play the game for more than an hour or so before wanting to go outside and see undestroyed civilization. I wanted to see the sun. I wanted to see smiles. That being said, I had to keep going. There was no way I wasn’t going to finish the game, and when I did, I was treated to a powerful ending.

White hairs in Joel’s beard, realistic facial animations, snow in Ellie’s hair, toy stores with identifiable toys. There’s a scene later in the game in which you visit an old ranch. Ellie has run away, and you go looking for her. You’re never entirely relaxed in this adventure, but you let your guard down for a moment when you walk in and see one of the most beautiful settings in a game. Many of us have been in a house like this, or seen one in movies. The hallways seem grandiose. The rooms are bigger. The open layout means very few doors on the main floor, yet no lack of privacy. The furniture still retains the charm of your grandmother’s old couch that you used to sit on while waiting for her and your mom to finish talking. The light. The light! The beautiful, rare, precious sunlight streaming in from the windows means a sharp contrast from the claustrophobic, terrifying annals of flooded hotel basements and sewer hideouts. That kind of detail doesn’t come by accident, you feel how intelligent the design is, and you fully believe the world you’re in.

If The Last Of Us is going to leave an imprint on future game design, it will be for the better. I don’t know how many desperate, emotionally draining games I can play before avoiding them altogether, but I do know that the attention to detail is something I would be privileged to see again.