The goal of the Serotonin column is to write about how games make us feel. I draw upon my relatively extensive experience playing games over the years and try to find good examples that will show that video games are more than just brainless, immature forms of entertainment. They have to be. Too many smart people play them, too many passionate people are involved making them and too many industrious, eager, educated, wild, thoughtful and persistent people talk about them with just as much enthusiasm as fans of books, movies, theater, sports, television, music and art.

Since starting in June, I’ve been waiting for a game to defy all my expectations on an emotional level. I’ve played some games that are fun, but don’t really help me expand upon the human emotion; games like Diablo III, Borderlands 2 and The Last Story have their merits, but none of them pack any kind of psychological punch. I didn’t question the reason why I was a tiny ship blowing up asteroids in Super Stardust HD. I didn’t bat an eye that I controlled five bizarre critters in the Monty Python-esque world of Botanicula. I played through Dragon Age: Origins (finally) and appreciated some elements, but the role of a Grey Warden didn’t keep me up at night. I didn’t have the need to shout out loud about how incredible Max Payne 3 was, nor did I Facebook everybody I knew telling them that Tales of Graces f was the must-play game of the year. There were certainly moments where I wasn’t sure I would find the game I was looking for, and I would have to resort to eroded memories of the past to give examples as to why games make us feel.

Thank you, Telltale.

The Walking Dead is the perfect example of why I have to write Serotonin. I need to tell gamers and non-gamers alike that video games can make us connect with fictional characters just as strongly as other mediums. They can make us feel guilty, or smile, or laugh, or cry. Many will scoff at this notion. Games to them are nothing more than toys for children, and those adults who never grew up (bless them). But I would challenge anybody to play through The Walking Dead and claim they didn’t feel anything. At this point, I might even think it’s impossible. They’d have to be an emotional wasteland, because Walking Dead is not only my game of the year, it is one of the greatest game experiences of my lifetime. It made me feel, something so few games do or even attempt.

I’ve never been one to avoid spoilers; most of my articles require explanation to give the readers an idea of why a particular scene, or character arc is important. I cannot avoid spoilers in this article, so I warn you now: if you haven’t finished all five episodes and plan to, stop reading immediately. The choices I made in the game may not be the ones you choose, but why take that risk? The game is short, cheap and beautiful. No excuses. Go play. If you have no desire to play, that’s fine. I’m honored to spoil 2012’s shining jewel for you. Let’s take a walk.

The Walking Dead is an episodic game from Telltale Games. Each episode is about a few hours long, and the complete package will cost you roughly $20 (worth it). It is adult-friendly, and by that I mean it’s friendly for those of us with jobs and children. Spouses. Responsibilities. The entire game is about 10 to 12 hours long, and perfectly manageable for those busy gamers who “don’t have time anymore.” Brownie points right off the bat.

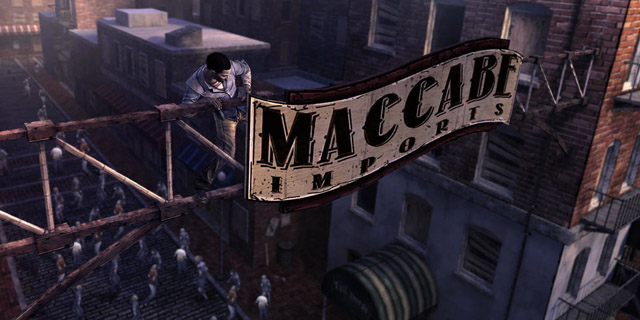

The game takes place in the same universe as the popular comic books and television series. There are a few crossovers. The graphical style is appropriate, as it looks like a living, breathing graphic novel. This is not a boring choice; each person’s features are elaborate enough to make them stand out and feel real, but not so much that they look goofy and cartoonish (Larry aside). You play as Lee Everett, a man convicted of killing a man who was having an affair with your wife. The game begins in the backseat of a police cruiser. I wouldn’t dream of telling you what happens next.

You wind up in the backyard of a house and you begin clicking on clues and walking around.

I have to take pause and warn you that the Walking Dead‘s major appeal is not in its gameplay. It is more of an interactive graphic novel. You will not get stuck behind puzzles, or massive action sequences. You can walk, point and click on objects in your area to examine or use them. This is the evolution of games like Day of the Tentacle and Sam & Max. Perhaps revolution is more apt a description.

So the gameplay is barely there, and it’s more of a choose your own adventure than a game. Why are you still gushing about it, you may ask?

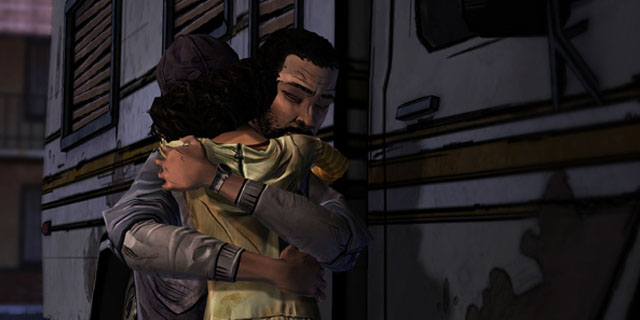

For starters (and more), there’s Clementine. She is the most crucial element of Walking Dead‘s success. She is a small girl you find in the backyard, hiding in her tree house. She’s adorable. She’s only eight, but she’s full of courage and wonder, apprehension and self-doubt. You know, like a real kid. Most children portrayed in entertainment are labeled as geniuses, or smart-alecks. They’re cartoons. Most are not based in reality. It’s very difficult to have a good performance from a child actor, so they have to resort to other options to get you to like them. Not Clementine. Your character realizes her parents aren’t coming back (two of the many victims of the outbreak… I did mention the game takes place during a zombie apocalypse, didn’t I?) and Lee offers to take her along and protect her. For an excellent parent-themed view on Clementine, see Justin’s piece on the subject.

Walking Dead‘s second major selling point is the decisions you make. You are constantly challenged with conversations questioning your choices, your leadership, your identity, your plan and what your thoughts are. Lee, who are you? Are you the kid’s father? Can you help us? It’s up to the player to tell the truth, lie or provide a vague response. Each choice is presented to the player clearly, but with a timer providing a wonderful amount of pressure. Not speaking is an option, but do you want to remain silent when your friend needs advice?

Your first devastating choice comes on a farm. A young man and a younger man are building a fence to provide protection against the zombies. They are both attacked. You have a choice: save Shawn or save Duck? At first, I thought I would be able to save both, so I picked Duck, the child. He’s a kid, and it looks like Shawn could get himself out of his predicament on his own. I soon learned that there are no easy choices in Walking Dead and no cop-outs. If you choose to save somebody, the other person is going to die. You’ll never see or hear from them again, and you’ll be reminded, no, haunted about why you picked Doug but not Carly. Doug himself might curse you for it later. Normally, you wouldn’t care if a non-playable character bitched at you for your decision, but the voice acting and writing are so realistic that every insult hurled your way will hurt. Every positive comment will boost your ego. Every time Clementine smiles and asks a perfectly rational question, you will beam and answer as nicely as you can. In a world where survival is a matter of question instead of certainty, you don’t always have the luxury of being nice or staying neutral.

Each chapter provides five major decisions. The game doesn’t prompt you about which decisions are the major ones, but it’s pretty obvious. Another stroke of genius comes from how Telltale keeps track of all decisions by people around the world and it lets you know which side of the fence you fell on with your decision. Holy crap, 72% of people chose to amputate Lee’s arm. Wow, this decision must have been tough, because the stats are nearly 50-50. The game’s developers have told us that there have been widespread, heated debates among gamers as to what decisions were the “right” ones. Each side totally convinced that the other side had chosen incorrectly. Telltale can also tell how long a major decision takes people, so even if a statistic might be heavily favored to one side, it might be the most difficult and controversial decision in the game based on how people waited until the very last second before making the decision.

This kind of argument doesn’t spring up much in the world of video games. Some arguments about who is the strongest character to take with your party will take place, sure. Or the best strategy for taking down a boss. But the choices present in Walking Dead, at their core, are completely moral and ethically questionable choices that anybody can sympathize with and have an opinion on. After all, it’s not Lee’s decision to take Clementine with you on a dangerous raid. It’s you. It says something about you, the player. Each decision can come along with an explanation of why a player chose it. Sometimes they’ll change their minds, or feel doubt about their decision. And the best part is that both choices could absolutely be considered the right thing to do.

After letting the ending sink in after a few days, I started up my next game on my list: Killzone 2. After listening to extremely stereotypical and uninteresting marines shout expletives and make homophobic jokes while shooting an insane amount of bullets and trudging through a world that hasn’t discovered any color other than grey and brown, I was insulted. I just didn’t care. Sure, I’d go through the levels and enjoy the challenge of a firefight. But I wasn’t interested in the characters at all. I don’t even remember what my main character’s name is. Your main allies, for some reason, don’t wear helmets, so you can see how tough they look all the time.

The Walking Dead might have ruined games for me.