Genre 101 is a series that looks at the past and present of a game genre to find lessons about what defines it. This week, Shawn guides us through what may be the oldest genre of them all.

The first serve

Shawn Vermette: Everyone has heard of Pong; it might be the most ubiquitous video game in existence. But it wasn’t the first sports game. Tennis for Two, which was made way back in 1958, holds that honor. In fact, Tennis for Two was arguably the first video game ever. It’s a fitting distinction, given that sports lend themselves so well to the video game medium. Using an oscilloscope, since monitors didn’t even exist back then, two people could hit a ball back and forth over a net using basic analog controllers. That was basically it, but it was over 20 years before anyone was able to surpass it in complexity.

Shawn Vermette: Everyone has heard of Pong; it might be the most ubiquitous video game in existence. But it wasn’t the first sports game. Tennis for Two, which was made way back in 1958, holds that honor. In fact, Tennis for Two was arguably the first video game ever. It’s a fitting distinction, given that sports lend themselves so well to the video game medium. Using an oscilloscope, since monitors didn’t even exist back then, two people could hit a ball back and forth over a net using basic analog controllers. That was basically it, but it was over 20 years before anyone was able to surpass it in complexity.

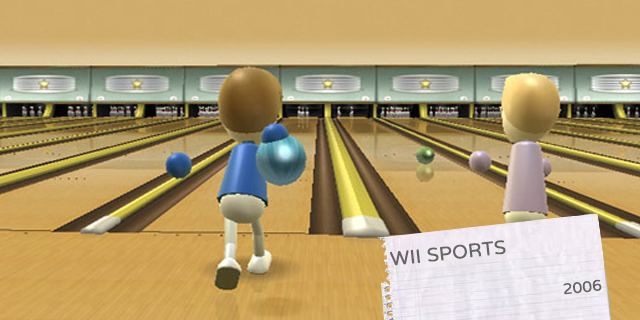

Graham Russell: It’s a reminder that, even though some take a few more steps than others, every genre has its roots in real life. Sports are the easiest and most transparent translations. The reason Wii Sports (which we’ll get to later) resonated so strongly was that it was the closest to the real thing, and thus the easiest to understand. It’s this link that makes games work. Would we even have games at all without sports games?

Graham Russell: It’s a reminder that, even though some take a few more steps than others, every genre has its roots in real life. Sports are the easiest and most transparent translations. The reason Wii Sports (which we’ll get to later) resonated so strongly was that it was the closest to the real thing, and thus the easiest to understand. It’s this link that makes games work. Would we even have games at all without sports games?

We certainly would, but the early days of gaming would have been much rockier, as developers slowly worked out an entirely new medium without such an easy conversion from something people recognized. Mechanics likely wouldn’t have developed as quickly either, as many of the most common that are used across a variety of genres originated in the early sports games.

We certainly would, but the early days of gaming would have been much rockier, as developers slowly worked out an entirely new medium without such an easy conversion from something people recognized. Mechanics likely wouldn’t have developed as quickly either, as many of the most common that are used across a variety of genres originated in the early sports games.

Skill, speed and endurance

In 1983, Track & Field showed up in arcades and later on the NES with a completely different way of playing sports games. Up until then, pretty much every sports game was a Pong clone of some kind, utilizing a very passive, reactive set of mechanics. Track & Field required players to take an active role in the game, with manual dexterity deciding whether you were successful or not. Rapid alternating taps of the two run buttons and an action button allowed your athlete to succeed in the various events it featured, from the javelin throw to the 100-meter dash and the long jump. Track & Field also revolutionized the genre via its content. Each sport was essentially a minigame, taking mere seconds to finish an event and move to the next.

In 1983, Track & Field showed up in arcades and later on the NES with a completely different way of playing sports games. Up until then, pretty much every sports game was a Pong clone of some kind, utilizing a very passive, reactive set of mechanics. Track & Field required players to take an active role in the game, with manual dexterity deciding whether you were successful or not. Rapid alternating taps of the two run buttons and an action button allowed your athlete to succeed in the various events it featured, from the javelin throw to the 100-meter dash and the long jump. Track & Field also revolutionized the genre via its content. Each sport was essentially a minigame, taking mere seconds to finish an event and move to the next.

Right! Track & Field was the first, and arguably purest, minigame collection. It’s a test of pure physical ability, just like the sport itself. This isn’t skill; it’s talent. It’s a good example of how diverse sports and their motivations can be, and that reminder is especially important to those who tend to write off the genre as a whole.

Right! Track & Field was the first, and arguably purest, minigame collection. It’s a test of pure physical ability, just like the sport itself. This isn’t skill; it’s talent. It’s a good example of how diverse sports and their motivations can be, and that reminder is especially important to those who tend to write off the genre as a whole.

Exactly! It’s important to note that many sports games require a level of physical coordination and ability, even now, to do well. Another early example would be the NES’ World Class Track Meet. You actually had to run and jump on a pad to beat your friends. Great technique and fast running trumped any video game skill.

Exactly! It’s important to note that many sports games require a level of physical coordination and ability, even now, to do well. Another early example would be the NES’ World Class Track Meet. You actually had to run and jump on a pad to beat your friends. Great technique and fast running trumped any video game skill.

A capable opponent

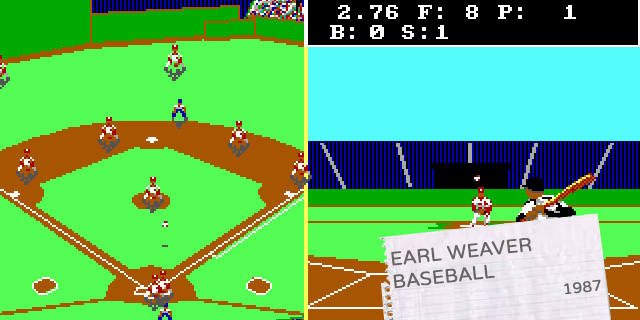

Over the course of the ’80s, developers were able to increase the complexity of games more and more. As the genre developed, it became increasingly important to allow for games where there were more players than people playing. Without a competent AI, games built around baseball, football or soccer would never be great. Earl Weaver Baseball was the top performer in the 80s, with a strategic and situational AI that was programmed using the knowledge of an actual baseball manager. The competency of the computer provided the baseline for sports games even a decade later, and many aspects of Earl Weaver Baseball are still used in present-day baseball games.

Over the course of the ’80s, developers were able to increase the complexity of games more and more. As the genre developed, it became increasingly important to allow for games where there were more players than people playing. Without a competent AI, games built around baseball, football or soccer would never be great. Earl Weaver Baseball was the top performer in the 80s, with a strategic and situational AI that was programmed using the knowledge of an actual baseball manager. The competency of the computer provided the baseline for sports games even a decade later, and many aspects of Earl Weaver Baseball are still used in present-day baseball games.

Sports are about player agency more than any other type of game. Platformers rely on simple enemy patterns. Shooters are more about enemy reaction. A sports game that’s “solvable,” one that has opponents on auto-pilot, isn’t very compelling at all.

Sports are about player agency more than any other type of game. Platformers rely on simple enemy patterns. Shooters are more about enemy reaction. A sports game that’s “solvable,” one that has opponents on auto-pilot, isn’t very compelling at all.

The repetition involved with playing a sports game virtually requires an intelligent opponent to make it worth playing more than a few minutes. Any specific action will be taken dozens to hundreds of times in any single game. There’s no fun at all in that if everything is predetermined on your opponent’s part. The introduction of a complex AI in sports games allowed every genre to make a great leap in complexity over the next generation.

The repetition involved with playing a sports game virtually requires an intelligent opponent to make it worth playing more than a few minutes. Any specific action will be taken dozens to hundreds of times in any single game. There’s no fun at all in that if everything is predetermined on your opponent’s part. The introduction of a complex AI in sports games allowed every genre to make a great leap in complexity over the next generation.

Stars, on and off the field

When Tecmo Bowl arrived, sports games were a fairly niche market with limited staying power. Tecmo Bowl instantly broadened the appeal with its focus on fast-paced action and direct competition. While it didn’t have team licenses, it did have real players, and each player on its twelve teams played differently based on real-life ability. The introduction of a playbook and realistic individual player stats set the tone for all future sports games, and the competitive nature of the game established a community of fans that has persisted to this day.

When Tecmo Bowl arrived, sports games were a fairly niche market with limited staying power. Tecmo Bowl instantly broadened the appeal with its focus on fast-paced action and direct competition. While it didn’t have team licenses, it did have real players, and each player on its twelve teams played differently based on real-life ability. The introduction of a playbook and realistic individual player stats set the tone for all future sports games, and the competitive nature of the game established a community of fans that has persisted to this day.

It was also the beginning of virtual celebrity. Bo Jackson, with his one running play, reached a level of electronic stardom that exceeded his (not-insignificant) success on the field. He wasn’t the last, with guys like Jeremy Roenick and Michael Vick enjoying near-invincibility in NHL ‘94 and Madden 2004, respectively. Are games more fun when they’re more accurate, or are these aberrations part of the charm?

It was also the beginning of virtual celebrity. Bo Jackson, with his one running play, reached a level of electronic stardom that exceeded his (not-insignificant) success on the field. He wasn’t the last, with guys like Jeremy Roenick and Michael Vick enjoying near-invincibility in NHL ‘94 and Madden 2004, respectively. Are games more fun when they’re more accurate, or are these aberrations part of the charm?

You can’t forget about the nigh-unblockable Junior Seau in Tecmo Super Bowl 3, either. That’s a tough choice for many sports fans, and I think there’s room for both in sports games. While realism is generally the ultimate goal of most of them, it’s always fun to find a player who is unstoppable force when you apply video game logic.

You can’t forget about the nigh-unblockable Junior Seau in Tecmo Super Bowl 3, either. That’s a tough choice for many sports fans, and I think there’s room for both in sports games. While realism is generally the ultimate goal of most of them, it’s always fun to find a player who is unstoppable force when you apply video game logic.

The over-performing icon

The early days of sports games involved wildly varying levels of realism in gameplay, but it wasn’t until NHL ‘94 that any major sports franchises reached a level of quality that enabled developers to focus on minor adjustments and improving the off-court game modes that the sports genre is known for today. NHL ‘94 was such a remarkable achievement in mechanics that it is still considered one of the best hockey games today, even used for many skills competitions at conventions.

The early days of sports games involved wildly varying levels of realism in gameplay, but it wasn’t until NHL ‘94 that any major sports franchises reached a level of quality that enabled developers to focus on minor adjustments and improving the off-court game modes that the sports genre is known for today. NHL ‘94 was such a remarkable achievement in mechanics that it is still considered one of the best hockey games today, even used for many skills competitions at conventions.

It’s also an example of a sports game exceeding the reach of the sport’s appeal. Many who weren’t exactly hockey people played NHL ‘94, and as a result, it was hockey for a lot of people. Do sports games, then, serve a role as a teaching tool for the rules and strategies of the sport itself, as well as a fun activity for those who already know them?

It’s also an example of a sports game exceeding the reach of the sport’s appeal. Many who weren’t exactly hockey people played NHL ‘94, and as a result, it was hockey for a lot of people. Do sports games, then, serve a role as a teaching tool for the rules and strategies of the sport itself, as well as a fun activity for those who already know them?

They definitely can serve that purpose. My earliest knowledge of football and hockey came from Tecmo Super Bowl 3 and Wayne Gretzky Hockey. When the gameplay is accurate and accessible, it can serve as a marketing tool for the sport as well as an enjoyable experience for established fans.

They definitely can serve that purpose. My earliest knowledge of football and hockey came from Tecmo Super Bowl 3 and Wayne Gretzky Hockey. When the gameplay is accurate and accessible, it can serve as a marketing tool for the sport as well as an enjoyable experience for established fans.

Over-the-top arcade action

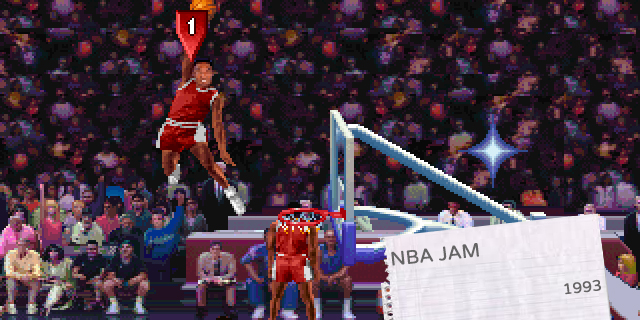

Over the course of the ’90s, sports games became more and more accurate, but not everyone was happy about that. Cue NBA Jam, which turned established convention on its head by purposely being extremely unrealistic. While other games had gone this route before, like Super Baseball Simulator 2.000, NBA Jam so perfectly captured the feel of a party game with its fast-paced ridiculousness that it brought about an entirely new sub-genre of sports games. While Jam had a professional license, it didn’t rely solely on real basketball players for its roster, giving players the chance to play with presidents, mascots and even the developers themselves.

Over the course of the ’90s, sports games became more and more accurate, but not everyone was happy about that. Cue NBA Jam, which turned established convention on its head by purposely being extremely unrealistic. While other games had gone this route before, like Super Baseball Simulator 2.000, NBA Jam so perfectly captured the feel of a party game with its fast-paced ridiculousness that it brought about an entirely new sub-genre of sports games. While Jam had a professional license, it didn’t rely solely on real basketball players for its roster, giving players the chance to play with presidents, mascots and even the developers themselves.

NBA Jam was the first, and probably best, game to exceed genre appeal and find fans among those who explicitly don’t like sports games. It was really just a theme! You know, like Super Mario Bros. is about plumbing. The result is a game that made every single one of the featured players into game icons, and you really can’t say that about any other sports game.

NBA Jam was the first, and probably best, game to exceed genre appeal and find fans among those who explicitly don’t like sports games. It was really just a theme! You know, like Super Mario Bros. is about plumbing. The result is a game that made every single one of the featured players into game icons, and you really can’t say that about any other sports game.

When NBA Jam came out, there were maybe a half dozen players that everyone recognized regardless of fan affiliation. But due to the popularity of NBA Jam, and the fact that every single team was capable of being competitive, tons of second-tier stars like Shawn Kemp, Tim Hardaway and Hakeem Olajuwon reached new heights of popularity among NBA fans.

When NBA Jam came out, there were maybe a half dozen players that everyone recognized regardless of fan affiliation. But due to the popularity of NBA Jam, and the fact that every single team was capable of being competitive, tons of second-tier stars like Shawn Kemp, Tim Hardaway and Hakeem Olajuwon reached new heights of popularity among NBA fans.

Turning seasons into franchises

With the arrival of the Super Nintendo and the Sega Genesis, sports games had more power than ever at their disposal, and Tecmo was the master of using it successfully. While Tecmo NBA Basketball and Tecmo Major League Baseball upped the ante in graphics, player control and stat tracking within a season, Tecmo Super Bowl 3 brought those improvements together with more off-the-field features than ever. You could create custom players at any position and place them on a team, with each player improving their stats based on in-game performance. The biggest improvements for most people were the addition of a free agent market, a trading period at the beginning of each season and a multi-season mode. Trades and free agent pickups carried through each season, allowing you to actually attempt to build a successful dynasty in such hopeless places as Seattle or New England. The ability to set every single team to a human or AI manager allowed groups of friends to compete, trade and fight over who would get to sign Deion Sanders.

With the arrival of the Super Nintendo and the Sega Genesis, sports games had more power than ever at their disposal, and Tecmo was the master of using it successfully. While Tecmo NBA Basketball and Tecmo Major League Baseball upped the ante in graphics, player control and stat tracking within a season, Tecmo Super Bowl 3 brought those improvements together with more off-the-field features than ever. You could create custom players at any position and place them on a team, with each player improving their stats based on in-game performance. The biggest improvements for most people were the addition of a free agent market, a trading period at the beginning of each season and a multi-season mode. Trades and free agent pickups carried through each season, allowing you to actually attempt to build a successful dynasty in such hopeless places as Seattle or New England. The ability to set every single team to a human or AI manager allowed groups of friends to compete, trade and fight over who would get to sign Deion Sanders.

Oh man, you know my weakness for franchise modes, and I’m not alone: there’s something special about managing teams over time. Fantasy sports can only take it so far; you want a complete, real context for your on-field team and its actions. The genre was forever changed; what was once a thing to sit down and play with a friend became one in which you could obsess over actions for weeks and months.

Oh man, you know my weakness for franchise modes, and I’m not alone: there’s something special about managing teams over time. Fantasy sports can only take it so far; you want a complete, real context for your on-field team and its actions. The genre was forever changed; what was once a thing to sit down and play with a friend became one in which you could obsess over actions for weeks and months.

Virtually every sports game since, if it has a professional license, has incorporated a franchise mode for exactly that reason. A single season mode is entertaining, but multiple seasons gives you the chance to create “what if” scenarios with your friends that can keep you occupied far longer.

Virtually every sports game since, if it has a professional license, has incorporated a franchise mode for exactly that reason. A single season mode is entertaining, but multiple seasons gives you the chance to create “what if” scenarios with your friends that can keep you occupied far longer.

Heading into the front office

Advances in hardware and the arrival of fully-connected computers allowed sports games to reach new heights of complexity in the mid-2000s with the release of Football Manager 2005. Players were given control of a soccer club and tasked with running it on every level, from match lineups to player contracts to training and international signings. It stripped away manual control of how a team performed on a play-to-play basis and replaced it with a management simulation that was unprecedented in size, containing hundreds of thousands of real players and dozens of leagues.

Advances in hardware and the arrival of fully-connected computers allowed sports games to reach new heights of complexity in the mid-2000s with the release of Football Manager 2005. Players were given control of a soccer club and tasked with running it on every level, from match lineups to player contracts to training and international signings. It stripped away manual control of how a team performed on a play-to-play basis and replaced it with a management simulation that was unprecedented in size, containing hundreds of thousands of real players and dozens of leagues.

Games like Out of the Park Baseball had been working on this management aspect, and even Madden had taken on lots of these kinds of functions, but Football Manager was the first to really give it an exclusive focus. It has become a phenomenon on its own, but more than that, it’s made such a minute level of detail in the functions of running a franchise an accepted and common part of even more mainstream games.

Games like Out of the Park Baseball had been working on this management aspect, and even Madden had taken on lots of these kinds of functions, but Football Manager was the first to really give it an exclusive focus. It has become a phenomenon on its own, but more than that, it’s made such a minute level of detail in the functions of running a franchise an accepted and common part of even more mainstream games.

Yeah, the focus on management as opposed to playing games was so popular that games like Madden and The Show have greatly increased the level of granular control players get when playing in a franchise mode, to their great benefit. More control, when handled well, is never a bad thing.

Yeah, the focus on management as opposed to playing games was so popular that games like Madden and The Show have greatly increased the level of granular control players get when playing in a franchise mode, to their great benefit. More control, when handled well, is never a bad thing.

Real skill, virtual action

The entire goal of the Wii’s motion-control scheme was to bring gaming back to the masses who’d been left behind by the growing complexity over the years. Wii Sports ably performed that goal better than anyone could have expected. There’s not a single person I’ve met who, when given the controller and set up in a tennis match, was unable to play somewhat competently and have a great time with it. Not surprisingly, sports games translate well to motion, and this success led to a plethora of other sports games getting the motion-control treatment.

The entire goal of the Wii’s motion-control scheme was to bring gaming back to the masses who’d been left behind by the growing complexity over the years. Wii Sports ably performed that goal better than anyone could have expected. There’s not a single person I’ve met who, when given the controller and set up in a tennis match, was unable to play somewhat competently and have a great time with it. Not surprisingly, sports games translate well to motion, and this success led to a plethora of other sports games getting the motion-control treatment.

Motion control, outside of sports (and, well, dancing), has had the problem of feeling wrong or tacked-on. Why it’s not a problem with sports is that it’s so inherently logical. Of course, at this point, there’s little chatter about motion control games, even with next-gen camera-based devices. Do you think the trend is really over? Can it be? Or is it just too natural of a fit to be a fad?

Motion control, outside of sports (and, well, dancing), has had the problem of feeling wrong or tacked-on. Why it’s not a problem with sports is that it’s so inherently logical. Of course, at this point, there’s little chatter about motion control games, even with next-gen camera-based devices. Do you think the trend is really over? Can it be? Or is it just too natural of a fit to be a fad?

Well-made sports games with motion controls will be popular as long as there are motion controls for systems. I think the boom period for them, when any game at all sold well regardless of quality, is far behind us by this point, though.

Well-made sports games with motion controls will be popular as long as there are motion controls for systems. I think the boom period for them, when any game at all sold well regardless of quality, is far behind us by this point, though.

Putting all the pieces together

Modern sports games strive to reach a perfect simulation of the real-life sport, and none has come closer than FIFA 13. Soccer has more subtle nuances in movement and play than any other major sport, and for this reason has always been more easily broken when technology has proven incapable of accurately reproducing them. It’s no small feat that EA was able to do so now, and I fully expect the advances that made it possible to influence design choices for the next generation of sports games. Another successful contribution? The Ultimate Team mode, in which players buy, sell or trade player cards, assemble teams out of them and then play against others with them. It seemed like a throwaway addition, but its popularity has skyrocketed and influenced similar modes in The Show, Pro Evolution Soccer and Madden.

Modern sports games strive to reach a perfect simulation of the real-life sport, and none has come closer than FIFA 13. Soccer has more subtle nuances in movement and play than any other major sport, and for this reason has always been more easily broken when technology has proven incapable of accurately reproducing them. It’s no small feat that EA was able to do so now, and I fully expect the advances that made it possible to influence design choices for the next generation of sports games. Another successful contribution? The Ultimate Team mode, in which players buy, sell or trade player cards, assemble teams out of them and then play against others with them. It seemed like a throwaway addition, but its popularity has skyrocketed and influenced similar modes in The Show, Pro Evolution Soccer and Madden.

It wasn’t that long ago the FIFA series was lagging behind Pro Evo. How did EA change that? Oh, you know, the kitchen-sink approach. It dumped tons of money into a super-nuanced on-field engine, an all-encompassing approach to league licensing and this Ultimate Team mode to let players truly obsess and collect. It set an even higher bar for peers like Madden and NBA 2K to clear: these days, you can’t just do some things right; you have to nail all of them.

It wasn’t that long ago the FIFA series was lagging behind Pro Evo. How did EA change that? Oh, you know, the kitchen-sink approach. It dumped tons of money into a super-nuanced on-field engine, an all-encompassing approach to league licensing and this Ultimate Team mode to let players truly obsess and collect. It set an even higher bar for peers like Madden and NBA 2K to clear: these days, you can’t just do some things right; you have to nail all of them.

That’s the same approach that allowed The Show to surpass MLB 2K as well. It takes a full-court approach for a sports sim to succeed these days. The good news for sports fans, of course, is that despite the common criticism of new games being simply roster updates, every year at least one game brings a great, new mechanic along that spreads across the genre.

That’s the same approach that allowed The Show to surpass MLB 2K as well. It takes a full-court approach for a sports sim to succeed these days. The good news for sports fans, of course, is that despite the common criticism of new games being simply roster updates, every year at least one game brings a great, new mechanic along that spreads across the genre.