Since its release in 2004, Friedemann Friese’s Power Grid (published in the US by Rio Grande Games) has been one of the top-ranked games on BoardGameGeek, currently sitting at #5. It has won several awards, each one generally coinciding with its release in a new language. Combining auctions, resource management, and route-building, Power Grid will tax the skills of from two to six players like few other games.

And I absolutely cannot stand playing it.

There’s just something about Power Grid that rubs me the wrong way. It might be its (estimated) two-hour play time, or it might be the fact that playing the game feels more like a math test than it does playing a game. Don’t get me wrong; I enjoyed myself a good math test back in the day. After I graduated some… uh… let’s just say “years” ago, they kind of lost their charm, and even before then, they were never my idea of a fun way to spend free time.

Power Grid uses a board based on an actual country, or group of countries in some cases, and each board has its own costs both for cities and resources. The board is divided into regions, the number of which are used in any given game being dependent on how many players are involved. Each city has three sub-spaces, each with its own (increasing) cost, and the cities are connected by pipelines with their own costs which are based on both proximity and obstacles (for example: connecting Boston to New York City costs much less than, say, connecting Salt Lake City and San Francisco).

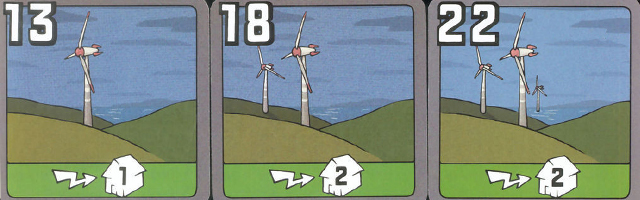

A double row of power plant cards serves as the auction market: the top four are the lowest-rated and are the ones currently available, while the bottom four represent the “futures market” and let players know what might be available in a future auction. I say “might” due to the fact that, when a new plant is drawn from the deck to replace a purchased one, it gets slotted in to the remaining seven based on its rating to keep only the four weakest available at any given time. A high-value plant might spend quite a while on the futures market before finally becoming available, if ever.

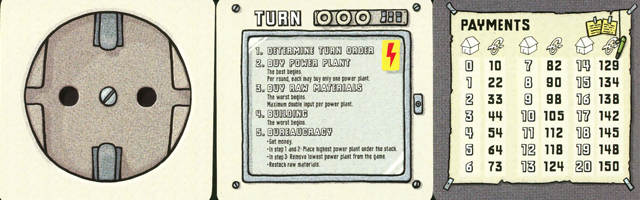

The game is broken down into three stages. The first stage lasts until one player has created a network of a given number of cities (again, based on number of players). Stage Two ends shortly after the “Stage Three” card is drawn from the power plant deck. Regardless of the actual stage, a round consists of the same five phases. Turn order is determined by the number of cities each player has, with ties broken by the highest-ranked power plant; many of the subsequent phases operate in such a way as to provide as many “catch-up” opportunities as possible. Power plants are then auctioned off, with each player being allowed to purchase only one plant a turn; players can only possess three plants at once, so upgrading is a necessity.

Next, raw material is purchased; these come in various flavors (coal, oil, trash, radioactivity) and are extremely limited, with the cost increasing as more are bought. Players cannot stockpile more resources than would be necessary to power each plant they own more than twice. Then building cities, with players having to pay for every connection they make in addition to the cities they establish; as mentioned, each city can only accommodate up to three players, and the number of players that can actually occupy a city at any given time is determined by the current stage of the game.

As you might have noticed, this is a lot of spending spread over several steps without an opportunity to earn cash, which is part of what makes the game feel so math-y. Planning out the most optimal route within the limits of what you can afford drags on and on as the game progresses. The final phase is where you earn cash, which is determined by how many of your cities you can actually “light up” with your plants and resources. After powering cities, the power plant market is adjusted based on the stage, and finally the resources are restocked (again based on stage and number of players).

This all continues until one player connects a given number of cities based on the number of players. The number of connected cities is only the end condition, however, not the actual win condition. The winner goes to the player who can power the most cities. Even though you have a network of fifteen cities, if you can only supply power to ten of them you will lose to someone who only has eleven but can power them all; cash is the tiebreaker, and only if that is a tie does total number of cities come into play.

Given these peculiarities, it is not unheard of for the player in the lead to hover just under the end condition while building up resources and/or improving power plants to ensure an ultimate victory, thus dragging out the game longer than necessary; more than a few games of Power Grid end when someone who has no chance of actually powering enough cities just rushes to the end condition to “put the game out of its misery”. New players also need to be aware that Power Grid absolutely revolves around being able to power your cities, as that is the only way to earn cash; if you fail to plan properly, you can find yourself unable to purchase the resources you need to do so and wind up completely shut out of the game. Winding up in such a predicament can seriously suck the fun out of your Power Grid experience, obviously, but is thankfully fairly rare and can only result in specific circumstances.

Despite my personal opinion (which is shared by several in my group), Power Grid can still be a fun experience. The strategy is deep, the mechanics are mostly clean, and the luck factor limited only to what power plants are drawn from the deck. Power Grid retails for around $50, although I highly recommend that you find a way to try a game or two and not just rely on word of mouth before purchasing. Expansion boards and decks are also available, so if you find that Power Grid is the game for you and your group you will be rewarded with several options if the base game has become stale.