I’ve covered a lot of worker-placement games in this column. Almost all of them use the mechanic of “first come, first served,” where placing one of your guys on a space will prevent others from doing so. Lancaster (designed by Matthias Cramer and published by Queen Games) twists this by giving each knight a strength of one to four, and letting stronger knights oust weaker ones for control of a given space. It’s not the only innovation Lancaster brings to the game table, but it is certainly the game’s defining feature.

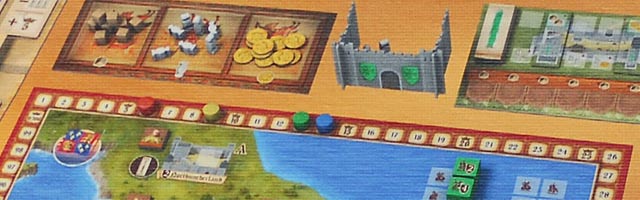

Of course, it helps that the different strengths of the knights are represented by more than just numbers. Stronger knights actually use taller wooden tokens than weaker ones. Even better, the token heights are proportional; if you stack a one-strength knight on a two-strength knight, the combined height will be exactly the same as a single three-strength knight. This is useful for determining the strength at a glance, and also adds a unique visual element to the game.

Knights can be placed in one of three areas on the board: the counties, your own castle and the battles. Counties are the actual worker-placement area described above. Each of the nine counties has a minimum strength requirement (often jokingly referred to as a “height requirement” like an amusement ride’s restriction) that must be met to even place a knight there. Players may use squires to add strength to any single knight placed there, but the knight itself must meet this requirement on his own. Beaten knights return to their players for new placement later on, but squires are lost once spent. At the end of the round, the knights controlling each county receive either the support of that county’s noble or the reward that county offers (or both, if the player pays some gold coins).

Your castle board has six spaces on it that bestow minor rewards (such as coins or squires) at the end of the placement round if they are activated. Each player begins the game with one banner that overlays a space and automatically activates it each round, and can earn additional banners through various other rewards. Otherwise you’ll have to place a knight if you want your castle to generate a specific reward, although sometimes there isn’t much other use for a one-strength knight that has been shut out of every county and is either shut out, useless, or superfluous in the battles.

At the beginning of each round, two battle cards are dealt to the appropriate spaces, representing the strength of the French forces and the rewards for defeating them. Three spaces accompany each battle, and a given player’s knights can only occupy one of those spaces, stacked on top of each other as necessary. The first six knights sent off to battle will award a King’s Favor to their player, with each favor being a one-time bonus each round.

If the collected strength of knights meets or exceeds the strength of the French, whoever sent the strongest group of knights receives the largest reward and so on down the line with ties being broken in the favor of the player who entered the battle most recently (thus turning the tide). If they don’t beat the enemy, however, that battle and all knights assigned to it slides down to the lower position for the next round and lesser awards are given out. A failed battle in that lower position will spell defeat, and any knights there are lost unless their owner pays for their return, which can be quite costly if you’re not careful.

Placing knights is the first phase of each round, while receiving the rewards from the counties, castle and battles, and the third through fifth, respectively. In between comes the Parliament phase, in which the players vote on three new laws that will affect some or all of them should they be enacted. Each player begins the game with a “yes” tile, a “no” tile, and a single voting cube. The tiles themselves are worth one vote each, as is each cube contributed to a vote. Unlike the tiles, cubes are not reusable, nor can they be carried over from round to round.

Since the number of cubes each player has for a given round is public knowledge, but everyone casts their votes at the same time, the whole is some sort of blind bidding/voting hybrid, which is has strategic implications if you want certain laws to pass and others to fail. A passed law (receiving more “yes” votes or a tie) replaces the oldest one on the board, and then whatever three laws are standing give out their bonuses as appropriate. Additional vote cubes are awarded only at the end of each round, based on the number of nobles supporting that player.

Nobles are also a major source of points once the game is over, after the fifth round. You can only win the support of each noble once, and the total number of players each noble can support is one less than the number playing so you have to choose wisely when controlling a county. You also score bonus points for having the most-developed castle (using gold as a tiebreaker) and/or the strongest array of knights (using squires as a tiebreaker). Oddly, there is no tiebreaker for actually determining the winner of the game, but that’s a minor problem at best.

A game of Lancaster supports two to five players, with special rules included for a two-player game, and is usually done in about an hour. Most of that time is spent in the placement phase each round, as players jockey for control of each county, which is easily the best part about the game. Everything else is incredibly quick, which smartly keeps the focus on the placement aspect which, in turn, determines how the other phases play out in a nice bit of synergistic design.

The main problem with Lancaster? Well, those precision-cut wooden pieces aren’t cheap, and there are quite a few of them per player, not to mention the wooden squire tokens, voting cubes, and start player indicator. Add to that the various cardboard bits and screens and you wind up at a game that might be too expensive for its (gameplay) weight, retailing at $65. I like the game, but for that price I’m looking for a more Agricola-class game (which itself cost $70), and I’m not sure Lancaster reaches that (admittedly lofty) level. Definitely try it for yourself if you can, and make your own judgment on that before buying.