The Secret of Monkey Island‘s insult sword fighting. The Walking Dead‘s zombie apocalypse. Myst‘s linking books. All are simple concepts at the center of great adventure games. 1954: Alcatraz adds “escape from Alcatraz” to that list. It manages to draw the player in, not only because a prison escape is impressive, but because escaping from Alcatraz is especially daunting. It’s not all cinderblock walls, corrections officers and time in solitary confinement, though. While Joe is working to break out, his wife Christine is doing her part around San Francisco to unravel the mystery of Joe’s armored truck heist and aid his escape in any way possible.

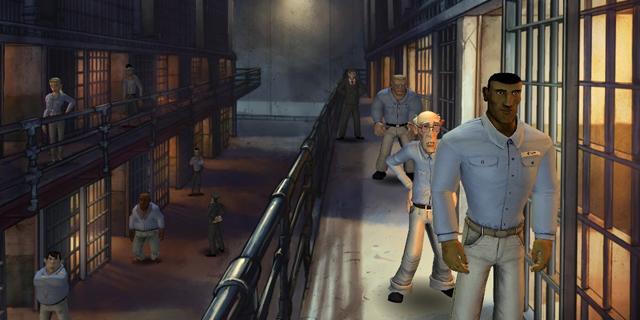

Playing 1954: Alcatraz feels like reading a pulp mystery novel. Characters are distinct, memorable and fun to interact with. I never want to meet a guy named Gas Pipe in real life, but Joe’s interactions with him are spot-on, and he’s a believably scary guy. He doesn’t have claws like Freddy Krueger or a hockey mask like Jason Voorhees; he’s just a guy with a short temper who yells at his wife who snapped one day at work. And that’s what makes him scary. I see a guy wearing claws or a bloody mask, and I know to stay away. I can see that he’s dangerous. We all know people with short tempers, though. The realism adds to the atmosphere, and giving side characters more back story than “I’m here for murder” really helps to make Gene Mocsy’s take on Alcatraz and San Francisco feel believable and alive.

There are some mechanical upgrades present in 1954: Alcatraz that I’d love to see become standards of the genre. Holding down the space bar highlights every object and person with which you can interact. Right-clicking gets you a description of the item or person, and left-clicking lets you interact. I love that I can hold down the space bar when I’m stumped to check for things that I missed, instead of banging my head against the wall while the story grinds to a halt and I trade in my adventure game for a hidden-object game instead. It’s a time-saver, and it shows that Daedalic understands that finding the phone transistor isn’t the fun part — using it is.

Switching characters is fun, too. Getting to escape Alcatraz and take control of Christine before Joe has any idea how he’ll get out himself gives us a glimpse of why he wants out, who is waiting for him and what she’s dealing with while he fixes washers and makes deals in the yard. It strengthens the narrative to control both suffering parties, as well as creates interesting puzzles and scenarios where the two work together despite all of the prison regulations in the way.

What I’d love to see, however, is the narrative put on rails a little bit. Switching between characters on a whim seems neat, until you get it and are never sure if you’re really done here for now. Did I miss something in the prison? Am I stuck because the story needs Christine to push it forward? Or did I just fail to combine my inventory items correctly and use them on something a screen or two over? Break the tale up into discrete chapters, so that I’m confident my time with Christine is done when I swap over to Joe (and vice versa).

Puzzle solutions make sense as well. Pay attention to your conversations and interactions, and you’ll never have a “why does the rubber chicken work here?” moment. Items aren’t always used for their intended purpose, but solutions make sense in context, and I never felt like the game expected me to make huge leaps of logic to progress.

A hint system would be appreciated, but I think that’s a truism of the genre more than a mark against 1954: Alcatraz, because when I’m stuck in an action game I still have action things to do. When I’m stuck in an adventure game, it’s just me and my thoughts wondering how to get out of this mess. And for a game about escaping from prison, the parallel hit too close to home. Just because there’s nobody around to help Joe doesn’t mean I couldn’t use a disembodied voice telling me to “look around for something to open that lock, dummy!”

Pros: Space bar to see interactables, interesting story, great setting

Cons: Never sure if it’s time to switch characters, no hint system