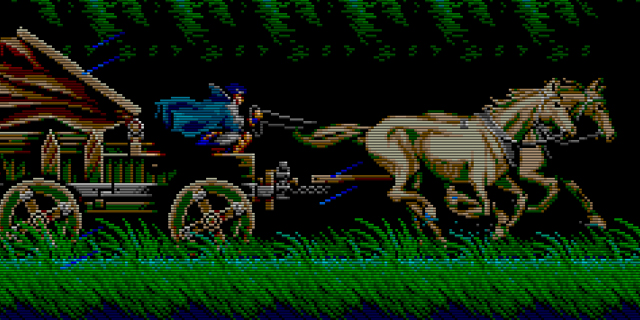

Unfazed by the raging storm, a hooded figure rides a horse-pulled cart at an incredible speed through the forest. His determined gaze and muscular appearance give away his Belmont lineage; his honed skills making him notice the grim shadow pursuing him. Throwing the reins and grabbing his family-honored whip, he quickly prepares for his dire situation.

It has been less than a minute since you turned on the game, and you’re already facing the Grim Reaper.

Akumajo Dracula X, also known as Rondo of Blood, is the last of the Castlevania platformers. Locked in Japan for almost twenty years after nonexistent Turbografx sales made an international release infeasible, most people recognize the game only in passing, thanks to the opening stage of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, which was its direct sequel, missing out, be it by price or ignorance, on what may very well be the most cinematic of all the Castlevania games.

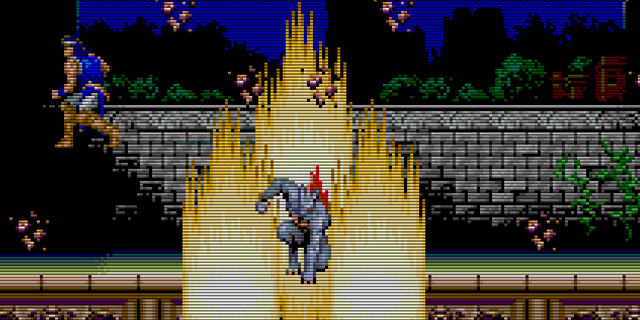

And this is not a shallow way to praise the game. This is not a game that tries to be a movie; it’s a game that lets you take part in one, putting you right there in the action and sucking you into its action-filled world. It’s Castlevania without the humility; it’s rash and bright. Even if it’s also a little bit disconnected at parts, you can really see it trying to push the narrative envelope of the series, really trying to make the game much more than just pushing the buttons with the appropriate timing.

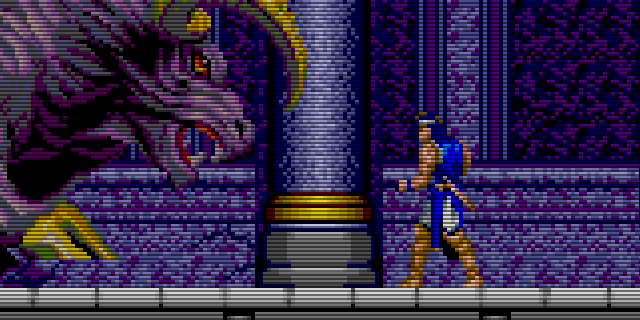

This is probably why the game is actually less of a platformer and more of a boss-rush, and it makes for a better tale. Zombies and skeletons are now relegated to a supporting role, letting you catch your breath after fighting with a wolfman or before killing the dragon that guards the gate. The game wants to be bigger and meaner, and even the nondescript birds of the original game have been replaced by feasting ravens whose grim presence alert you of danger right as the amazing CD music gets louder and louder.

In some ways the game remembers me of Half-Life, adding small tricks of narrative to a usually dry genre. Both games don’t conform themselves with being good in a mechanical way. Both want to have a more lively setting and to really make what is on the screen great to see.

Powered by an underpowered 8-bit processor but greatly enhanced by the CD add-on, the game manages to best the offerings of its contemporaries. It’s better-looking than anything on the Genesis or SNES, with huge sprites and scrolling backgrounds that left players in awe not because of the technical advancement, but because of the amazing art direction itself. In fact, the rectangular pixels of the console add that ounce of retro charm to the very nice graphics more than being a nuisance, and I can really appreciate that. Sure, you could do away with the anime interludes and some of the voice acting, but the overall package is so good I can barely consider them a flaw.

While the game itself (and especially the console) are outside most people’s budget, thanks to the lasting success of Symphony of the Night, Konami saw fit to release it for the Wii’s Virtual Console, which offers a great experience for a much reduced price and practically no hassle other than using the Wii itself. Alternatively, you can try the PSP remake, which doesn’t look as great, but also includes Symphony of the Night and the original graphics once you beat the game.