Modern boardgaming has no shortage of awesome new titles arriving on store shelves every month, but digging back to explore the roots of the hobby can be just as rewarding. This past week I was introduced to Reiner Knizia’s Medici, a game first published in 1995; I realize with no small amount of angst that this date quite possibly makes the game older than some of you reading this column (or at least your younger siblings), but for me that date is forever tied to graduating from high school.

Medici is, put simply, a game about bidding. You start with a certain amount of points (representing florins/cash), and you bid those points to purchase one or more good tiles. At the end of each round, you then earn points back based on your overall cargo load and how well you are monopolizing the market, which you then turn around and have to bid again to get more goods in the next round. It’s a great distillation of “you have to spend money to make money,” with the trick being how to properly evaluate how much each given shipment of goods is worth to you in the long run. Each player also receives a ship board with five cargo holds, which is where they put the tiles they have purchased.

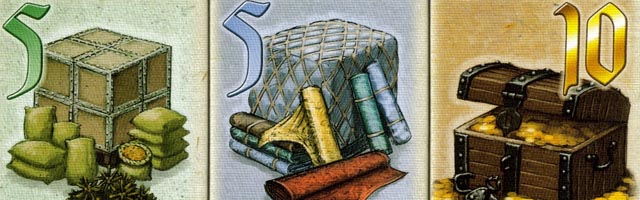

The good tiles come in five varieties plus one giant stack of gold. Each variety has tiles valued from zero through five (with two five-value tiles), while the gold tile is valued at ten. At the beginning of each round, some tiles are randomly removed from the mix in secret (similar to No Thanks!), so that the total available is six per player (a six-player game would remove nothing). The start player then pulls out tiles one at a time until they either are satisfied with “shipping” all of the tiles pulled, they have drawn a number of tiles equal to the highest number of empty spaces on all players’ boards or they have drawn three tiles. Then, starting with the player on that player’s left, the bidding begins.

This isn’t auction-style bidding, however. You just name your price in turn and the highest bid wins, with the player who drew the tiles getting the last say. If nobody bids on the tiles, that player can either purchase the entire lot for one point or trash them, then pass the bag of tiles to the next player to repeat this process. If there is only one player with empty spaces on their board at this point, they fill out the rest of their cargo with tiles drawn randomly (if any remain) and pay nothing for them.

There are a number of factors that need to be considered here. On the most basic level, you need goods to score points. Each tile of a given color you have collected (regardless of that tile’s value) moves you up on that color’s track, but only the two players with the most in each color (cumulative over the course of the game) will earn points, so you really need to specialize when possible. If you’ve done really well at this you will score bonus points, and if you do that well early enough you’ll get those bonus points each round. Pinning the needle on a given good with eight tiles will earn you a staggering twenty bonus points (plus the ten you will almost undoubtedly get for being first in that color) in both rounds two and three, which can be enormous, but there are lesser rewards of five and ten bonus points that can also be earned along the way. Of course, you only have room for five tiles each round, so none of those bonuses are available in the first round.

On the second level, you can also get points for having the highest-valued total cargo each round, with the actual reward again being dependent on the number of players. This is determined by adding up the values of all your tiles for that round, and where the ten-valued but otherwise worthless gold tile comes into play. Everyone but the lowest-valued boat will earn something, but the rewards for being first could be worth taking a slight hit to your specialization. Then you have to realize that there are only so many tiles in the bag. If enough of them (or any, in a six-player game) get trashed, there won’t be enough for everyone to fill up their cargo holds, which could definitely hurt when it comes to tallying up.

Of course, those are the obvious issues: the scoring ones. The strategic issues, however, are what make the game interesting. How many tiles do you pull out of the bag when it is your turn to do so? If you pull out more tiles than a player has open cargo spaces, you effectively shut them out of the bidding that round. If you pull out a tile that someone else really wants, do you want to maybe try and “poison” the offering by drawing something they don’t (similar to loading the trucks in Zooloretto), knowing that you could wind up making the shipment even more enticing instead? What if you pull out a tile that you really want? Drawing an extra tile then might just be greedy and wind up backfiring, but how high are the other players going to jack up the price before you get to finally make your bid on it? Of course, they can’t go too high or you might just make the last one eat a bunch of points for a tile (or tiles) they don’t even really want… but could they turn that around and start moving in on your monopoly? And what about the bonus points for largest boat? And so on.

As with most of Knizia’s best designs – and this man is one of my all-time favorite game designers – the simplicity of the design hides some intriguing decisions. And since the game is only three rounds of this simple gameplay, it moves incredibly quickly, easily under an hour per session. I have only played twice so far and I want to explore it more. For instance, both of my games were with five players, which meant that almost all of the tiles were available. I bet the game changes significantly when there are only three or four and it is harder to depend on specialization to deliver big points. For that matter, we played under the World Boardgaming Championship rules that ignore the five-bonus space, which could also make an impact on how the game plays out and is probably more important in games with fewer players.

There are a few minor flaws with the game, or at least the edition of it that I played. Two of the goods, wheat (yellow) and pelts (white) can be hard to distinguish by their color alone, especially on the score track, and the tiles for silk (blue) and spices (green) can have similar problems depending on lighting conditions. The wooden scoring pieces themselves, shaped like sacks of coins, are slightly too big for the spaces on which they have to move, and can sometimes slip into a different space if players aren’t careful when moving them. But these are extremely nit-picky concerns for an otherwise amazing game, and ones that might not even exist depending on which edition of the game you use. Considering that this game is approaching its twentieth anniversary, there are certainly enough editions to choose from, and with no in-game text it doesn’t even matter what language your version’s rulebook is actually written in.

Medici retails for around $40.